Leslie’s Guiding History

A Guide to Guiding History, in the UK and beyond.

- Notes

- Timeline

- Traditions Badges

- The Sections

- Rainbows

- Brownies

- Guides

- Rangers and Young Leaders

- Guiders

- Commissioners/Advisers/Trainers

- Trefoil Guild/LINK/SSAGO

- Lone Guiding

- Guiding for Members with Disabilities

- Guides at War

- International

- Promise Badges

- Interest Badges and Awards

- Six/Patrol Badges

- Camp/Holidays

- Outdoors

- Music/Arts

- Religion/Beliefs

- Lists

- Profiles

- Flags

- Training Centres

- World Centres

- How To’s

- Guiding Fiction

- What Did They Do in the 19__’s?

- History Resources

- Teaching History

- Historian’s Corner

- Uniforms

- Royal Guides

- Logbooks and Notebooks

- FAQ

- Gallery

- UK Guiding Magazines 1910s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1920s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1930s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1940s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1950s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1960s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1970s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1980s

- UK Guiding Magazines 1990s

- UK Guiding Magazines 2000s

- Policy, Organisation and Rules

My name’s Leslie and I’m an ordinary Leader in Guiding who happens to be interested in Guiding History . . .And that’s why I’ve decided to set up a website with information to help other people who are interested in Guiding history too. So whether you’re looking for information towards the traditions-linked Unit Meeting Activities, working on the Commonwealth Award, or just interested in a particular section or era, or just to answer a query you haven’t found the answer to anywhere else, I will try to help.

I have also set up two sister websites, one focusing specifically on what Guides did during World War I and World War II – www.lesliesguidingwarhistory.com – and one focussing on badges and their syllabuses, at www.lesliesguidingbadgehistory.com

Each of the websites costs me hosting fees, which come out of my pocket. If you find the websites helpful, please consider using the button at the bottom of the page to make a donation.

As well as being a constant ‘work in progress’, with new pages being added when possible, and more information being added to the existing pages as my research uncovers new discoveries and insights – this site is strictly unofficial, simply my attempt to fill a gap which I felt existed. Because when I set it up, there were very few Guiding history websites online, and many of those there were contained errors or myths. So some of the content will necessarily be a personal viewpoint – but even those who can honestly say ‘I was there’ about an event or an era will recall things differently, or give greater significance to differing aspects to those I’ve picked out – it isn’t easy fitting 110 years and counting of history on one website! As you will appreciate, there are some costs involved in running a website of this size, and travelling to do the research work – these currently come out of my own pocket. Should you wish to make a contribution, I would appreciate use of the payment option below.

I will try to acknowledge contributions in the ‘news and notes’ section, but if you think there is an omission or an error, then please contact me so I can take prompt steps to clarify or rectify as appropriate. If you have any information to offer, suggestions for content you would like to see, or questions you would like to have answered which I haven’t covered, then please let me know. I will see what I can do – many of the pages or passages follow requests!

How Guiding Started

Let’s start with the basics. Robert Stephenson Smyth Powell was born in London, in on 22nd February 1857. He was the son of Baden Powell (a clergyman and university professor), and his much younger third wife, Henrietta Grace Powell. When Robert was 3 years old, his father died, and when he was 12 Henrietta changed the surname of herself and her children (only, not the step-siblings from their father’s previous marriages) from Powell to Baden-Powell, to commemorate their late father. Robert was first educated at home, then at a local prep school, and then after much effort on his mother’s part he was granted a full scholarship which fortunately covered all school fees – as the son of a clergyman, this allowed him to go to Charterhouse, a well-known public school as a “Gown Boy Probationer”. There he did not shine academically (apparently at that time, applying yourself in lessons wasn’t the fashion – not a problem for students who would go home to run the family estate regardless, risky for those like Robert who would need a career). He was more successful at of out-of-class activities including sport, acting, etc. During his second year at the school, when he was 15, it moved from central London to a rural site in Godalming, Surrey. There hadn’t been time to prepare sports pitches at the new site before the term started, so the boys had more free time than normal during the summer term that year. There was a nearby area of out-of-bounds woodland which Robert regularly broke bounds to explore that term, occasionally trapping rabbits and building small camouflaged cooking fires to cook them on, hiding from patrolling masters where necessary by climbing the trees – because most searchers didn’t look up! Of course, by the following term the pitches had been prepared and the scope to explore the woods was reduced. Summer holidays were often spent sailing or camping and exploring in the countryside with his adult brothers, while the expensive family home in a fashionable area of central London was let out for the season, to save money.

He had hoped to follow his older brothers to university, but despite attending crammers and taking several resits, his consistently poor exam results made this impossible despite his mother’s best efforts to promote his cause. Short of suitable options for someone of his social class, he applied for the army, and his very high marks in the Cavalry exam (and officer shortages at the time) meant that he was among a small group of recruits who were appointed directly as officers and posted abroad immediately, without first attending officer training school as would normally be required – this was just as well for him, as officer training school would have meant academic exams he would not have been able to pass. He spent many years in the army, mainly in Africa and India (he preferred foreign postings as the officer’s lifestyle was more affordable abroad than it was in the UK). During that time he developed his reconnaissance skills (then usually called scouting), and wrote some army training manuals including ‘Aids to Scouting’ for use by other army officers seeking to teach these skills to the soldiers under their command.

Following his role in the long and successful defence of the town of Mafeking against the besieging Boer army, Robert returned home to Britain as a national hero and celebrity. As a result of his new status and profile, many individual boys and boys’ clubs wrote to him, asking for advice on varied topics. He also accepted an invitation to become involved at a senior level in the Boys’ Brigade organisation, which had been founded some years before – and he wrote a booklet of ideas on scouting and backwoods skills for Boys’ Brigade Officers to incorporate into their programmes (though this doesn’t seem to have been much taken up by them). Over time, he increasingly thought that the outdoor exploring he got up to with his brothers during school holidays, and the scouting and spying experiences he had had in the army, could be attractive and useful pastimes for modern boys of various classes, and could enhance the activity programmes of existing boys’ clubs – even though several articles he had written on the subject had come to naught.

He decided instead to test out the theory for himself, in July 1907, by running an experimental camp with boys from different social classes. Half the boys were sons of his upper-class friends, and the rest were all local boys of working or middle class background drawn from the Boys’ Brigade in Dorset (it can be confirmed that, contrary to some accounts, absolutely none of the campers were from the East End of London, as a list of participants exists). He was loaned the use of Brownsea Island in Dorset, the camp was a great success and drew positive media coverage, and after it Baden-Powell was enthused to start on re-writing his army manual in order to create a book of ideas suitable for leaders of boys’ clubs to put outdoor adventure into their club programmes – titled ‘Scouting for Boys’.

Baden-Powell’s publisher, Arthur Pearson, decided to issue the book initially as a fortnightly part-work, from January to March 1908, with the full volume following in July, to maximise the sales. The by-product of this serialisation was that, at four old pence each fortnight, the instalments of the war hero’s new book were affordable for boys to buy from their pocket money if they clubbed together – and buy them they did! So across the country, boys bought these chapters, turned their loose gangs of pals into Scout Patrols, dressed as close to the described uniform as they could muster from their wardrobes, and headed for the nearest public park, farmer’s field or common to try out the suggested adventurous activities and exciting games for themselves.

Girls also got hold of the part-work in much the same way, and many of them soon formed Patrols too. After all, in Scouting for Boys it did say “Scouting is equally suited to boys and girls”, so the hint was there . . .

A flood of queries and requests for Scout equipment and badges meant that a structure for Scouting was urgently needed, so during 1907 Baden-Powell set up a headquarters in Victoria Street, London, with an office and an equipment depot, to supply the massive demand – and many private firms rushed to fill the gap, manufacturing uniforms – and all sorts of fascinating accoutrements too!

The new official magazine, “The Scout” started on 14 April 1908, and helped to link troops and answer queries, and a further camp (what could be considered the first actual ‘Scout Camp’) was held at Humshaugh in Northumberland in August 1908, with places allocated through a coupon competition run in ‘The Scout’.

Baden-Powell travelled right across the UK addressing specially-arranged public meetings about Scouting, seeking to explain the purpose and benefits – these speeches drew a great deal of enthusiasm, and were effective in recruiting many Scoutmasters and Scouts for the movement – both boys and girls. The public meetings were often widely publicised beforehand, and reported on afterwards, sometimes verbatim, in local newspapers.

As records show, at this time Baden-Powell was clearly supportive of Girl Scouts. In May 1908 he wrote to one Girl who enquired that she would be welcome to set up a Patrol of Girl Scouts, and in his regular column in ‘The Scout’ in January 1909 he stated of the girls that “some of them are really capable Scouts” – and in the 1909 edition of Scouting for Boys the uniform guidelines stated that Girl Scouts should wear navy skirts. Large Scout Rallies were held, including one at Scotstoun near Glasgow, where Girl Scouts were both specifically invited, and warmly welcomed. So clearly, throughout 1908 and much of 1909, Girl Scouts were welcomed, and welcomed officially at that.

On 4th September 1909, Baden-Powell held a national Scout rally at the Crystal Palace in London, which had been widely advertised through regular full-size front-page articles in ‘The Scout’ magazine for many weeks beforehand. These articles urged all Scouts to apply for tickets to attend, and for as many troops as possible to offer to perform Scout skills in the main arena. Thousands of Scouts ordered their tickets in advance as instructed, both boys and girls, and travelled miles to get there – and it is reported that more than 1000 Girl Scouts were present.

One small group of Girl Scouts from Peckham Rye only decided to go at the last minute, too late to apply for tickets. Having arrived well after the start time (since some of the group hadn’t managed to bring money for bus fares, they had opted to all hike, and it took them far longer than they had allowed for), and having no tickets they opted to march straight through the gates at full pace, in the hope that no-one would try to stop them – in other words, to literally gatecrash. So they formed up round the corner from the gates, then got up speed and marched round and straight in through the gate and up to a space by the rope barrier, before anyone could stop them! Some time later, Baden-Powell and the other Scout Officers came along to formally inspect the various Patrols and Troops of Scouts who were present. Probably due to having heard something of their cheeky exploits, Baden-Powell gave a rather frosty reception to this particular bunch of Girl Scouts, but nevertheless reluctantly agreed to let them join the tail of the march past which was held at the end of the rally. (This is the incident which has been incorrectly described by some as the first ever encounter between Baden-Powell and any Girl Scouts, and equally incorrectly as an indication Baden-Powell didn’t approve of the idea of Girl Scouts at all, rather than what was far more likely to be the case, a Lieutenant-General disapproving of the un-Scoutlike antics of this particular group). Other groups of Girl Scouts took part in the body of the parade, as usual.

Still, pressure was starting to build for something to be done about the Girl Scouts, rather than let things drift on as they had so far, thus in the November 1909 edition of the Scouts’ Headquarters Gazette magazine the ‘Scheme for Girl Guides’ was published. It was perhaps a wise move. Up until then, media coverage of Scouting had been generally favourable, though there was some local difficulties in some parts of the country, most of which had been dismissed by Headquarters blaming it on copycat, or ‘monkey patrols’ as they tended to term those groups who dressed up in similar clothes but weren’t registered and didn’t try to live within the rules laid down by the Scout Promise and Laws. Then in December a row started up in “The Spectator” magazine with various correspondents responding to a letter from Miss Violet Markham in which she described the activities of a mixed troop of Boy and Girl Scouts in her locality, who apparently were going on troop hikes without any female chaperones and returning home as late as 10 pm, as well as holding their troop meetings together in a Drill Hall to an equally late hour with no adult females present – there were several responses to the letter which described Girl Scouts as ‘mischevious and improper, unfitting the future housekeepers of the nation for their predestined state; a glorified skylarking, which will militate against the pursuit of the domestic arts, in which women, in every walk of life, are so scandalously deficient’. In publishing Miss Markham’s initial letter, the editor of The Spectator had stated “We heartily endorse Miss Markham’s protest. Not only is scouting work most unsuitable for girls, but if it is persisted in it cannot but ruin a movement which may well prove of immense advantage, moral and physical, to the nation, – a movement for the making of good citizens. We desire, then, to appeal most earnestly to General Sir R. S. S. Baden-Powell to stop this mischevious new development. Even if he does not agree with this protest, he will, we trust, see the wisdom of not jeopardising the cause of the Boy Scouts by setting public opinion against them, as he most certainly will by insisting on this mad scheme of military co-education.” At the time a great deal of media attention was being given to the direct-action activities of some militant suffragettes – and there were some signs of Girl Scouts being inadvertently thought of as associated with suffragette ideas by some members of the public, simply by being a group which was both providing, and encouraging, more opportunities and freedoms for girls than society had granted them to date. This negative media publicity, and the risk of it causing damage to the growing good reputation of the fledgling Boy Scout movement, may well have been what really persuaded Baden-Powell of the need to do something specific about the girls who had joined Scouting, rather than just let things drift on as they had done so far – especially as by now it was no minor matter – amongst the official Scout membership of 55,000 there were already over 6000 known Girl Scouts officially registered, and more registering daily!

Hence the Boy Scouts’ management took steps to try to manage the publicity, while behind the scenes, steps were being taken to find a solution. One clear sign of this is the letter from the Managing Secretary of the Boy Scouts, J Archibald Lyle, to the editor of The Spectator in response to the series of correspondence initiated by Miss Markham – “Sir, From recent correspondence in the press on this subject there appears to be an impression that Girl Scouts form part of the organisation of Boy Scouts. I am directed to state that this is not so. Mixed troops of boys and girls are not countenanced in our organisation. There are some small irresponsible imitations of the Boy Scouts movement about the country, and it is known that in certain of these mixed troops have been started. We are much indebted to Miss Violet Markham for drawing attention to this, since unless it is under very good supervision the system is open to grave objections. Of course it is impossible for the public to discriminate between the different bodies alike in dress, and the blame has naturally fallen on the Boy Scouts. All we have done has been to register and take note of the large number of girls who have applied to us as anxious to take up scouting; and in view of their keenness and of the good that some such movement might obviously do, especially among a certain class of girls, a suggestion for Girl Nurses (called “Guides”) as an entirely separate organisation has been made by Sir Robert Baden-Powell to the Red Cross Society, which it is hoped may be taken up by ladies’ Committees of that organisation where considered desirable. The aim of the scheme is to teach the girls hospital and home nursing, cooking, housekeeping, &c., by practical means, appealing to the girls’ own imagination and keenness. -I am, Sir, &c., J Archibald Lyle”

Baden-Powell had indeed tried contacting several of the first aid organisations to ask if they would be willing to take on and train the Girl Scouts as some form of junior nursing cadets – but none had been interested (perhaps because the type of girl who would join the Scouts, given the general air of disapproval for girls doing any such active activities, was naturally likely to be the more rebellious and lively sort!).

So, with that door closed, Baden-Powell then turned to his only surviving sister, Agnes, to form a separate organisation based on Scouting, but specially for the girls. Agnes took on the job reluctantly, possibly because she was naturally shy and did not care for the limelight – but perhaps also, because she could not be unaware of the difficulties of the job she was being asked to tackle. She would have to create a programme of activities which would satisfy the girls to whom the outdoor adventure of Scouting had appealed, the girls who were already tackling the hiking and exploring games contained in ‘Scouting for Boys’ with full enthusiasm and making plans to camp. But – it was important that the programme also obtained the approval of their Edwardian parents, renowned for their strictness, especially with daughters, and their near-constant instinctive fear of their girls being ‘led astray’ – and it was clear from correspondence such as that ongoing in The Spectator, that the new movement would be under a great deal of public scrutiny too. In those days, middle and upper class girls in particular led very restricted and sheltered lives – walks were sedate affairs, girls rarely went out unchaperoned, and some doctors still thought either physical exercise or academic work could permanently damage girls’ brains and health! Girls were also expected to stay at home to help with the running of the household, and practice appropriate, gentle hobbies such as needlework, watercolour painting and piano practice, whilst looking forward to the prospect of marriage and running a home, unlike their brothers who did formal academic school lessons, then in their free time got to hike, hunt and fish, and could look forward to an (albeit limited) choice of career.

Yet in many ways, though like Robert already in middle-age, Agnes was an enlightened choice. She had a wide range of hobbies and interests, and thus managed to create a programme of activities which steered a skilful middle path between what the girls wanted to do – and what their parents wanted to see them doing. She set up Guiding on a solid footing, and soon had a room rented for the office, and an executive committee staffed with keen, experienced, distinguished and influential lady charity organisers and fundraisers who were capable of quickly taking things forward – and whose clear support for the scheme also helped to demonstrate the respectability and appropriateness of the plans to nervous parents. Though Agnes herself was skilled in all the household arts expected of a well-bred lady of her generation, and had spent many years keeping house for her widowed mother – she was also involved in early aviation, both in balloons and in aeroplanes, and helped her younger brother with sourcing and repairing engines. Her hobbies included metalwork, bicycle stunt-riding, astronomy and camping – not a typical for a lady of that era.

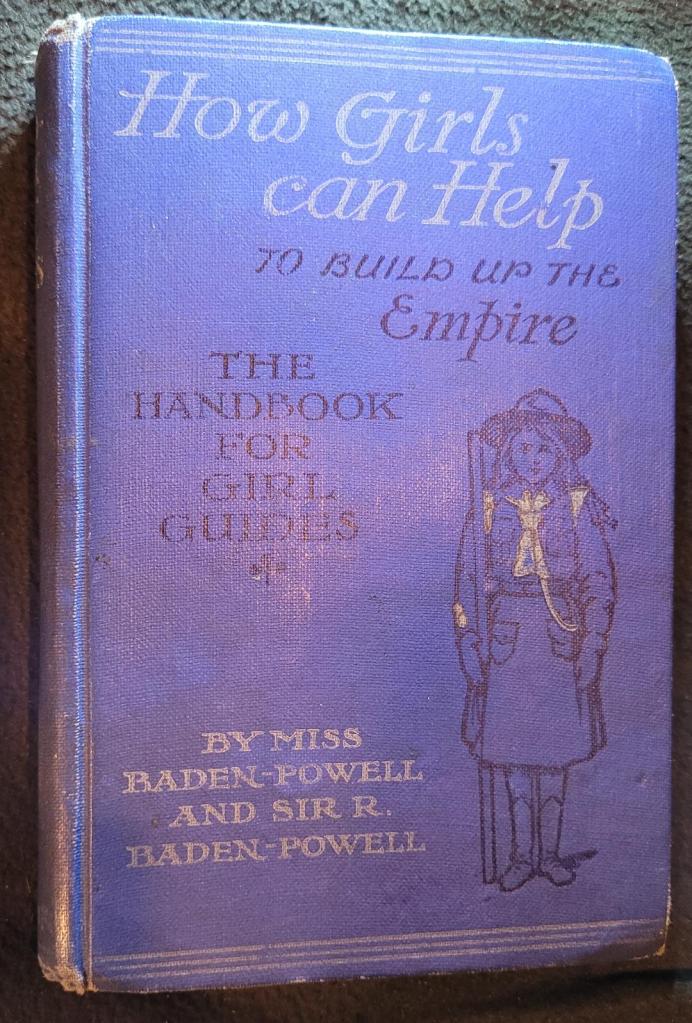

In May 1912, from ‘Scouting for Boys’, Agnes wrote ‘How Girls can Help to Build Up the Empire’. It contained many of the familiar Scouting activities the Girl Scouts had so loved doing, but carefully covered in a micro-thin veneer of feminine respectability. The adventurous outdoor exploring and camping was all still there, for she had skilfully dressed it up as preparation for frontier life in the far reaches of empire, where even respectable girls might have to learn to cope without the support of trained servants or professional help – but there was also a heavy emphasis on home skills, sick nursing and child care to appease the parents and assure them that becoming a Guide would not encourage the girls to neglect their home duties and responsibilities, indeed it would actually encourage them to develop their knowledge of these key skills. From her own knowledge, Agnes included a great deal of nature lore and household management too. Although it was a difficult balancing act, Agnes’ book contained an amazing range of detailed and valuable information on both the outdoor adventure and the domestic aspects of Guiding, and was a great success, attracting favourable reviews. One newspaper stated “An elaborate scheme of training, physical, moral, domestic, civic, and imperial is expounded in the book in a way that cannot but interest and stimulate girl readers.”

This was followed in 1914 by the launch of the “Girl Guides Gazette”, a monthly magazine for Leaders, to replace the single pages which had appeared in the “Home Notes” and “Golden Rule” magazines, and had been the only direct way in which Headquarters could contact units. The Gazette was aimed at Guides as well as Guiders, so contained a mix of training articles, rule updates and details of new badges, alongside fiction serial stories.

In October 1912, 55 year old Robert Baden-Powell had married 23 year old Olave St Clair Soames, whom he had first met 7 months before, whilst he was travelling by ship on a world tour for Scouting, and she was accompanying her recuperating father. Prior to meeting Robert she had known nothing of Scouting or Guiding, as she admitted herself. She soon became keen to be involved in Guiding, despite her lack of any youth-work experience and a somewhat patchy education which had ceased when she was 14 – that lack of experience meant she did not succeed in getting a senior role, so she opted to become involved in Scouting instead, starting up a Scout troop at her house with the assistance of her servants, and working as a volunteer at a rest hut for soldiers in France between having her children. In early 1916 she applied to Guiding again, and this time was successful in obtaining the post of County Commissioner for Sussex. Garnering the support of other young County Commissioners, and urging her friends to apply for any vacant County Commissioner posts across the country they could, she was voted in as Chief Commissioner in September 1916, then worked to gradually oust the existing committee members, whom she considered old-fashioned. (Agnes had naturally appointed mainly contemporaries, experienced charity organisers who could get a new organisation running from the difficult position of over 6000 registered members but neither structure nor funding – so the committee members were naturally older than Olave, then 27).

Agnes was forced aside into the honorary post of President (soon after, Princess Mary was appointed President, and Agnes was promptly downgraded to Vice President) and the membership of the headquarters committee Agnes had created was entirely replaced, in some cases despite members’ great reluctance to leave. In February 1918 the new handbook, “Girl Guiding” by Robert Baden-Powell had been brought out to replace “How Girls Can Help to Build Up the Empire”.

From that time, Olave Baden-Powell was both the public face and the private driving force behind Guiding, and Agnes was excluded from any meaningful involvement. Agnes is rarely mentioned in official publications, and was often not invited to events she might have been expected to attend, such as the World Camp in 1924 (she sneaked in anyway). Within a few years Agnes’ contribution was almost entirely forgotten, even to the extent that some people nowadays mistakenly refer to Robert and Olave Baden-Powell as ‘the founders’. Meantime, Agnes quietly continued her work with the Westminster Branch of the Red Cross, and many other charities and organisations.

In 1927 Olave Baden-Powell relinquished the post of UK Chief Commissioner, and in 1930 she was appointed to the newly-created role of World Chief Guide, a unique post she held for the rest of her life, and which ceased on her death. During the early 1930s both Robert and Olave undertook many international tours promoting Guiding and Scouting. Following some ill-health for Robert including heart problems, they moved to Nyeri, Kenya in 1938, as it was thought the warmer climate would benefit his health. The initial plan was that it would be a stay of a few months, but the outbreak of World War 2 prevented any possibility of a return to Britain, so they stayed in Kenya. Robert died in January 1941 at the age of 83, and he was buried there. Olave stayed on in Kenya for a further year to tie up loose ends and visit family, before returning to the UK.

Agnes Baden-Powell died in 1945, and was buried in the family grave in London, although her name was not added to the gravestone (a group is currently working to fundraise in hopes of rectifying this).

On Olave’s return from Kenya (her house in the UK having been requisitioned for war work in her absence) she was soon granted a grace-and-favour apartment at Hampton Court Palace, which served as her base when not travelling the world on behalf of Guiding – though in her later years that travel was restricted by her health. She finally moved to a nursing home in 1976, before dying in 1977, her ashes were then added to the grave in Kenya.

Guiding carried on growing, and in 2010 celebrated it’s Centenary Year, with Brownies then celebrating their ‘Big Brownie Birthday’ in 2014 and Senior Section their ‘Spectacular’ in 2016. In July 2018 new programmes were released for all sections in the UK, which were fully implemented from July 2019.

March 2020 brought another significant change in Guiding. An infectious virus, named Covid-19, started spreading around the world. Many countries, including the UK, introduced lockdowns for all of their citizens. The immediate result of this was that all unit meetings were cancelled, for an unconfirmed duration. All local Guiding meetings and events, too, had to be cancelled, as individuals were only allowed out to leave their houses once a day for exercise, and then only if they stayed 2 metres apart from anyone not in their immediate household. Units coped with this in a number of ways. For those whose Leaders were stil involved in working, it meant units temporarily closing down. Others were able to send out activities by email or on facebook groups; some were able to hold videoconference meetings online. During 2020 there were some periods where units were allowed to meet outdoors, provided everyone wore a fabric or surgical facemask, and kept 2 metres apart – but by the end of 2020 worsening infection rates meant this had to stop, and during late 2020 and early 2021 it was back to videoconference meetings or activity packs. The result of being unable to hold regular meetings was a significant drop-off in membership. Fortunately the situation improved, such that subject to conditions, units could meet indoors from August 2021, if they had the staffing and could find premises willing to host them – many halls remained reluctant to hire. Over the course of 2022, surviving units got back to normal. Restrictions were gradually eased, and a number of events resumed.

Then in March 2023 came the launch of the new logo, with new designs for Promise badges, letterheads, and section colours. June 2023 brought two announcements – firstly that British Guiding Overseas was to be completely closed down, then a week later, that all of the UK Guiding training centres were to be closed down. Campaigns promptly began against both of these decisions.

Running a website does cost money in hosting fees – other than donations received, the costs of the hosting fees, and of research trips to uncover more information, come out of my pocket. If you do feel able to contribute towards the work, this can be done using the form below.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly