The first guidance on camp organisation came in the 1912 handbook “How Guides Can Help to Build Up the Empire”. It gave elementary information on tents, catering, sanitation and activities, and on approaches to take with parents. Tents tended to be ex-army bell tents or ridge tents, hired, together with ex-army billies for cooking. Personal kit was minimal, indeed from modern eyes it was very scanty indeed.

At that stage there were no qualifications needed by Guiders to run camps, although it was one of only two activities which needed parental permission (the other being attendance at places of worship). Whilst many satisfactory camps were held, it seems that some may have been less well organised, as by 1921 new rules were introduced.

By the 1922 season, “Notes on Camping” had been published by the association. This was more than mere ‘notes’, being a booklet giving advice on all aspects. Guiders who wished to take their Guides to camp now had to pass the Guide Cook’s badge and be able to cook out of doors, and “Must show a knowledge of the arrangements which should be made before holding a Camp of any given number of Guides, for: 1) Choice of Camp site. 2) Contracts with tradesmen. 3) Storage of food. 4) Shelter and bedding. 5) Sanitary arrangements, including latrines, wash-house, and refuse pits. 6) Cooking. 7) Necessary equipment. 8) Drying and airing of bedding, etc. 9) Transport. Must draw up a list of Camp rules and personal equipment suitable for issuing to parents of intending campers. Must draw up: A programme of a day in Camp, giving reasons for the various activities, and including menus of meals. Or. A plan showing the organisation of the orderly duties for a week on the Patrol system. Must give a list of ten of the most useful articles suitable for stocking: 1) A medicine chest. 2) A dry canteen. Draw up a menu for well-balanced meals for a week in Camp, showing knowledge of food values and economy. Must have camped a week, or two week-ends, under canvas, and understand camp life in relation to woodcraft. Know how to pitch, trench, air, and strike a tent. Must understand Camp Hygiene and Elementary First Aid and Home Nursing in relation to camping. Improvise one Camp gadget and erect screening. Construct a Camp fire-place, erect a flagstaff, and know the ceremonial proper to the hoisting, breaking, and lowering of the flag.

1922 saw the introduction of Camp Directors for South England, Midlands, East England, Scotland, and Wales – they were tasked with examining and appointing a Camp Adviser (recommended by the County Commissioner) for each County in her area. County Camp Advisers were tasked with examining Guiders for the Camper’s Test. A ‘Camp Permission Form’ had been introduced, as well as a ‘Parents’ Consent Form’. It read: “Parents’ Consent Form. 1) A Camp for ___ will be held at ___ from ___ to ___. 2) Station ___. 3) Postal address ___. 4) Dr ___ of ___ has kindly promised to attend the Camp. If parents will fill in the following form they will be informed immediately in case of illness. 5) Bathing will only be permitted (with parents’ consent) at stated times and under strict supervision. 6) Fatigues. All the work of the Camp will be performed by the Guides themselves, working in Patrols, and everyone will be expected to do her share cheerfully and thoroughly. 7) Uniform will always be worn unless it gets wet, in which case it will be worn again as soon as dry. 8) Visitors’ Day will be on ___, when the Camp will be open to the public from ___ to ___ . On all other days the Camp will be strictly private. 9) Fees for the ___ will be ___ of which ___ must be paid to the Captain when the Guide applies for Camp. This cannot be returned in any case. 10) Health. No Guide should have been in contact with any case of infectious illness for at least three weeks before Camp, and parents are strongly advised for their own satisfaction to assure themselves that their girls’ heads and hands are perfectly clean. If all parents will assist the Captain in these matters of health it will insure their girls enjoying a happy and healthy camp. 11) Food. Guides will be expected to eat the food provided. No food may be kept in the tents. Please sign the following: I have read the above, and am willing for my daughter to attend the Camp and obey all orders as above. My Postal address will be ____. I do not believe my daughter to have been in contact with any infectious illnesses during the last three weeks, and I have done all in my power to insure that her head and hands are perfectly clean. Signed ___. Are there any points in your daughter’s health that require special care?”

Guidance was also given on sites: “Camp Sites. 1) Do not wait until summer to think about your Camp site; look around during the Winter, and, if possible, inspect the site at least six months before the Camp; and try and see it at it’s worst on a bad day. 2) Water. Be sure there is an adequate supply within 100 yards of Camp. Water from a main is preferable. Never trust surface water. Always have it tested when the site is first inspected, and, again, three or four days before the Camp. Find out the history and source of any water not from a main. 3) Wood. There must be a good supply handy, or fuel will have to be used for cooking. 4) Shelter. The Camp should be sheltered by trees on the N. and S.W. If possible, camp on a slope open to the S.E. The ideal site is on a S.E. slope, pine woods or a hill for shelter on N. and S.W.; situated on a good loam; within 100 yards of water; near a bye-road; and with a good barn for use in wet weather. 5) Screening. If there is not an abundance of natural screening, canvas must be used for latrines, and wash-houses, and may be camouflaged as far as possible. 6) Kitchen and Latrines. Must be situated to leeward of the Camp and in a downstream direction. 7) Owner of Site. Interview him before the Camp and tell him in detail what you want to do. (1) Number of tents; (2) exact measurements of the trenches you wish to dig; (3) get permission to collect wood and make fires. 8) Trades People. Interview the local trades people, and arrange for delivery of stores, etc. Dont’s. 1) Don’t camp on clay or in a hollow, both are sure to be damp. 2) Don’t camp on rock, as it is impossible to drive in the tent pegs, or dig trenches. 3) Don’t camp near lakes or ponds, as it will be damp, unhealthy, often rocky, and the home of mosquito. 4) Don’t camp on sandy beaches, as the tent pegs will not stay in, also flies and mosquitos abound there. 5) Don’t camp near crew-yards or pig-sties. 6) Don’t camp near public-houses or main roads.”

“General Hints for Holding a Camp.

1) The Captain must be in close touch with her Guides, and know that she can really trust them before taking her Company to Camp.

2) Pay minute personal attention to every detail, the health and happiness of the camp may depend on it.

3) Size of Camp. One Guider cannot manage more than a Patrol Camp, for a Company Camp it is essential to have at least three Guiders: (1) Captain and Commandant, (2) Quartermaster: To look after the stores and cooking. (3) Orderly Officer: To organise the games, fetching, taking, and distributing of letters; attend to any Guide who is ill.

4) Go and see the local Doctor before the Camp and ask him to attend you in the event of any illness or accident.

5) Bathing. Never let beginners and those who can swim bathe at the same time. Have a picket of good swimmers on the bank, who do not go into the water until all the others have gone out. Examine the bathing place carefully beforehand for rocks and holes. In the case of sea bathing, the shore often changes after each high tide, especially on the East Coast. If possible mark off a safe place with ropes floated on buoys, and anchored with tins filled with stones. Always have a boat or raft, the latter can easily be made and floated with empty petrol tins; nine tins will float a 6 ft. raft. Never bathe sooner than 1 1/2 hours after food.

6) Health. Have a Red Cross tent, in which there should be a bed, medicine chest, and the name and address of the local Doctor. Have a head inspection within the first hour of Camp. If anything is found, immerse the infected head in neat methylated spirit, and repeat in 24 hours. A head inspection must be done privately, and by the Captain herself.

Impetigo. Skin disease in blister form with heads that break. Dress with lysol, 1 in 20 solution. Make the Guide wash in your tent, and keep her washing materials and towels. Let her look after the wood etc., and have nothing to do with the food.

Look for constipation on the second day in Camp, and give as much fruit as possible. A good plan is to mix Epsom salts with the eating salt, half and half.

7) Keeping Clothes. Never let any clothing, boots, etc., be on the ground, either at night or during the day. The clothes worn nearest the skin must be put under the pillow, at the foot of the sleeping bag, or in a suit case during the night. The top clothes will keep dry if hung on hangers as high up the pole as possible.

If Guides have mackintoshes they are much better than thick coats. Worn over a jersey they are quite as warm, and in wet weather they do not become sodden and difficult to dry.

8) Always have a barn or marquee for use in wet weather, and let it be large enough for games, drill, and country dancing. Let the Guides run about with bare feet in wet weather while they are working, but when they sit down for meals, or come into the barn for games, etc., make them dry their feet at once, and put on dry shoes and stockings.

After a wet day, take round hot drinks after the Guides are in bed, and if any seem very cold put their feet in hot mustard and water. If any are very wet, rub them down first. A small dose of amoniated quinine is sometimes a good thing after a wet day. Boots well done with dubbin keep out the wet. To dry wet boots, stuff with newspaper or put hot stones in and shake them round, care being taken that they are not hot enough to burn the leather.

9) Prayers. Have these every morning, after the hoisting of the Union Jack and before personal inspection. They may be held either before or after breakfast; if the former, each Guide must have a biscuit first. Have five minutes silence for evening prayers, about 20 minutes before ‘lights out’.

10) Patrol System. Run the Camp on this system, and let the Leaders have a chance of teaching their Patrols. Give the Patrols woodcraft names.

11) Courtesy. Camp is the best opportunity of teaching this; let the Guides behave properly at meals; don’t let them cross other tent doors without first asking permission of the occupants.

12) Food. Never let the Guides keep any food in their tents.

13) Canteens. Have a canteen daily at 11 am for the sale of cocoa, lemonade, sweet and plain biscuits, plain and milk chocolate, and good boiled sweets; note paper, post cards, pencils, note books, stamps, hair ribbon, shoe laces, needles, darning wool, tape, cottons, etc.

Impress on Guides:

1) To leave gates as they find them. 2) Never to walk across growing crops. 3) Never to climb fences except by a stile. 4) Never to roam about woods without permission, on account of game. 5) Never to cut trees, branches or hedges without permission. 6) Never to light a fire without permission. 7) Always to leave any camping ground as though they had not been there.”

By 1933 the first edition of “Campcraft for Girl Guides”, subtitled ‘the Official Camping Handbook’ had been published. By this time Guides had been camping for 20 years, and yet the opening paragraph read “People are still to be met with who hold up their hands in horror at the idea of Camp. ‘Sleeping on the ground – in a field! Aren’t you afraid?’ ‘Of what? Damp, tummy pains (caused by amateur cooking) or midnight visits from a ghostly quadruped?’” Guides might have been running camps for over 20 years by that time, but the task of reassuring the public clearly wasn’t complete! It also advised “It is not a good thing to go to the same site year after year. The place loses its freshness; the children know all its charms and peculiarities; and most of the feeling of adventure has vanished.” To find a new site, the advice is “Friends, especially those who own a park or fields, should always be attacked first. If they will not, or cannot, provide you with the perfect site, they probably can help you to procure it from a neighbour. You may wish, however, to go far afield into unknown country. Either your own Commissioner, or the one in whose district you wish to go, will in this case put you into communication with the nearest Camp Advisor, who is supposed to keep a list of all good camping sites in the neighbourhood.” In seeking a site, the essentials were considered to be soil, situation, shelter, water, distance (from home and from local amenities), space, fuel, and transport. Camp funds were a key topic – the advice given was “Every Guide should be expected to save something (however small) towards her camp fees. This may be augmented from other sources, as the Guider thinks fit. If economy has to be considered, it should not find a place in the Commissariat department. People who run camps are too fond of the idea that ‘anything will do’. There is no excuse at all for children not being fed well in camp. Prices are coming down and a party of over twenty can be fed excellently at the rate of 1/- to 1/3 per head per day. Of course, there will be many Guides who cannot afford this; but the money should be raised by other means, viz., entertainments, sales of work, or even donations.” Weekly savings scheme cards were also suggested, and it was suggested that “expense can be cut down if everything which can be made is made by the Guides themselves, viz., Palliasse covers, camp hats or bonnets, overalls and even a lean-to tent for the cook place.”

The Camp Equipment List was growing longer too. For a camp of 20 it was suggested:

5 or 6 ordinary sized bell tents – three for Guides, one for Guiders, one hospital tent, one for drying wet gear. Ground sheets – either individual ones 6 ft. x 3 ft., or circular in sections, which can easily be moved. Extra small ground sheets to sit on at meals. Screening poles, guy lines and pegs for washhouse, 3 stools for latrines, 6 lengths of wood to support seats, 3 tins for toilet paper, 3 American cloth covers for toilet seats, roofing for latrines, spade and pick axe, axe and saw, hammer and assorted nails, 3 trowels, course sand paper and drawing pins, latrine bucket, swab and scrubbing brush, 4 buckets for wash cubicles, 4 basins for washhouse, 4 small tubs or foot baths for washhouse, 3 washing up buckets for Patrols or one tub, short lengths of board for latrine trench, toilet paper, lysol and chloride of lime, 2 trestle table tops (legs would be lashed from gathered wood), extra rope, string and tent pegs. Camp notice board and letter-box. Camp work basket for sewing kit. Flag for hoisting. 2 lanterns. Store tent. 4 dixies. 1 steamer or fish kettle. Small saucepan. Large frying pan or baking tin. 2 pudding cloths. 3 7 lb. jam jars (to steam puddings in). 2 large knives and forks. 2 or 3 wooden spoons. Coarse grater for cheese and vegetables. 4 enamel or china bowls. 4 enamel or china jugs. 2 buckets for water. Colander. Basin or tub for washing-up unless done in Patrols. Saucepan cleaner, mop and swab. Large dishes for serving. Butter muslin. Pastry board and pin, or jar for rolling. Soap and soda. Bricks and iron grids for fireplace. 4 posts, tarpaulin or ground sheets, guylines and pags – for fire shelter and wood pile. Tin and wooden boxes for the stores. Tin opener and corkscrew. Extra knives, forks, spoons, plates and mugs. Salt and pepper holders. Wire netting for incinerator. Camp bed, soft pillow, hanging lamp or lantern, camp chair – for hospital tent. Carron oil for burns and scalds, iodine for cuts, Boracic powder, Zinc ointment for sunburn, Oil of cloves for toothache, Cinnamon and ammoniated quinine, Castor oil, Liquid paraffin, Epsom’s salts, ammonia for stings, adhesive plaster, roller bandages, cotton wool, Boracic lint, Jaconet, Thermometer, Hot-water bottle, Safety pins, Pair of scissors, 2 triangular bandages, Sal volatile – in first aid chest. Canteen – Chocolate (1d. and 2d. bars, good brand), Fruit drops, or good make of boiled sweets, Toffee, Peppermint bulls-eyes, Buscuits – sold at 2 or 3 a 1d., Fruit (not raw plums), writing paper, envelopes, postcards, black hair ribbons, shoe and boot laces, safety pins, pencils, still lemonade (made from lemons or powder). (Guiders are warned that it is illegal to sell stamps over the counter of the canteen.). Palliasse cover per person (bag about 6 ft. x 3 ft., it is best if the top has a flap which will button over like a pillow case. Plus 3 blankets.

Camp prospectus and kit list: “Company Camp of the ___ Girl Guides. Date: ___ to ___. Address: ___. Cost: ___ (inclusive or exclusive of transport fare). Transport: ___ (if by train, give time of train and station; if by motor, the time it will be at Company Headquarters. Also state how and where luggage is to be collected). Visiting day will be; ___ from: ___ to: ___.

1) The Guides will sleep in tents, on straw mattresses. Solid shelter has been obtained for sleeping quarters in case of wet weather. 2) The food will be good and ample. No food sent to individual Guides will be delivered. 3) The bathing will be under the strict supervision of a competent Life-saver. 4) No patent medicines may be bought. First-aid supplies when required can be obtained from ___ who is competent to deal with small accidents and sickness. 5) There will be 1 1/2 hour’s rest i nthe middle of the day. 6) Every care will be taken for the comfirt, health and well-being of the Guides, but the Captain cannot hold herself responsible for any accident which may occur.

Kit List. (Everything must be clearly marked in some way, so as to distinguish it. The Captain will not hold herself responsible for lost property).

1 palliasse cover – 6 ft. x 3 ft. (straw is provided). 2 blankets, at least, coloured if possible. 1 pillow case. 1 bath and 2 face towels. 1 glass cloth. 1 jersey, jumper or other woolly wrap. 1 extra skirt (any colour). 1 overcoat or waterproof. 3 pairs black stockings. 1 pair sandshoes. 2 pairs strong boots or shoes. 1 pair dark blue knickers. 1 change of underclothes. 1 pair warm pyjamas or nightgown. 1 overall or apron. Guide uniform. Camp overall. Handkerchiefs. Hair, nail and tooth brush and hair comb. Nail scissors. Soap, sponge or flannel. Tooth powder. 2 enamel plates. 1 small bowl (for soup). 1 enamel mug. 1 knife, fork, desert and tea spoons. Notebook and pencil. Signalling flag (if required). 1 extra black hair ribbon. small ball of string. Each Patrol can provide boot and badge cleaning outfits, a dish cloth, unless swabs are provided by the camp, and a mirror.”

“The good camper will have arranged at the very beginning of things for some place where wet shoes and clothes may be dried. But the golden rule is to keep as much as possible from getting wet. A bathing cap, a mackintosh and one pair of shoes each is the proper costume for a thoroughly wet day. No stockings, of course. But even so equipped it is advisable to keep as many Guides as possible under shelter in really heavy weather, and the kitchen shiould be well covered in to protect the cooks.”

The 1942 and 1944 editions of “Campcraft” had the same introduction:

“No attempt has been made to rewrite Campcraft in order to bring it into line with wartime camping. Guiders should remember that in all cases they must find out from their Camp Adivsers what are the restrictions put upon camping in the localities in which they wish to camp. All camps must be camouflaged and, as far as possible, hidden from view. Large camps are nowhere to be encouraged, and, where possible, camps should be held within easy reach of home. In dangerous areas access to some form of adequate shelter should be available. The responsibility of taking Guides to camp in wartime is offset by its increased value as training. In the small woodland camp so common to-day there are great opportunities for all forms of woodcraft. The difficulties of transport have reduced the amount of equipment generally taken, thus making for independence and ingenuity. Programmes have more room for wide games and the practice of all kinds of Scoutcraft than was the case in a large number of the seaside camps held before the war. The Guide whose wartime training includes camping will be the better equipped to face life. In spite of the great efforts that have been made to keep on camping under all difficulties, there has of necessity been a great drop in the number of those going to camp since the war. A complete generation of Guides to whom the joys of camp are a closed book would be a tragedy. Headquarters therefore looks with confidence to all Guides, knowing that they will do all in their power to carry on the great tradition of camping that our Movement has had in the past.”

Camp Programmes

The first guidance on programming for Guide Camps came early in Guiding’s history. The 1912 handbook, “How Guides Can Help to Build Up the Empire” gave a daily programme as well as activity hints. In these early days, a lot of inspiration was taken from army camp routines, including the posting of ‘sentries’ each night to guard the camp. The suggestion was:

06.30 am – Turn out, wash, air bedding, coffee and biscuit. Hoist Union Flag and salute it.

7 – 7.30 am – Parade for prayers, and physical exercise, or instruction parade.

7.30 am – Stow tents and tidy up.

8.00 am – Breakfast.

9.00 am – Scouting practice or signalling.

10.30 am – Biscuit and milk. Sundays to church.

11.00 – 1.30 pm – Scouting games or swimming.

1.30 pm – Dinner

2 – 3.00 pm – Rest (compulsory). No movement or talking allowed in camp.

3 – 5.30 – Scouting games.

5.30 pm – Tea.

6 – 7.30 pm – Recreation, camp games, first-aid practices. Prepare beds.

7.30 pm – 8.30 pm – Camp fire and biscuit and milk. Post sentries.

8.30 pm – To bed.

9.00 pm – Lights out.

Suggested camp activities included making a loom to create woven mattresses, shelter-building, pioneering, tree-felling, outdoor games and wide games, picnic hikes, swimming, and working on those Second Class and First Class tests suited to being doing outdoors. Although Guides did post sentries as Scouts did, for Guides the advice was “Captains should see that there is no raiding of camps Sentries can be posted to learn the duties but no Guides should no night sentry later than 9 pm.”

Swimming rules applied – “Bathing unders strict supervision to prevent non-swimmers getting into dangerous water. No girl must bathe when not well. Bathing picket of two good swimmers will be on duty while bathing is going on, and ready to help any girl in distress. This picket will be in the boat (undressed) with bathing costume and overcoat on. They may only bathe when the general bathing is over and the last of the bathers has left the water.”

By 1921, and the publication of ‘Notes on Camping’, the advice was:

“Programme for a Day in Camp

6.45 am – Cooks get up.

7.00 am – Rest of Camp gets up.

8.00 am – Breakfast.

9.30 am – Prayers and Personal Inspection, followed by Tent Inspection and Inspection of Orderly work.

10.00 am – Work of some kind, drill, etc.

11.00 am – Canteens. Work (Camp Craft).

1.00 pm – Dinner.

1.45 pm – Rest Hour.

3.00 pm – Court of Honour

3.15 pm – Free Time

4.00 pm – Tea

5.00 pm – Games, etc.

7.00 pm – Supper.

8.00 pm – Camp Fire.

9.00 pm – Bed.

9.45 pm – Lights Out.

Take the Guides out for long walks and picnics as much as possible, don’t ‘stick’ to camp for the whole week.”

Orderly Work for a Company in Five Patrols:

“Cooks – 1) Cook all meals. 2) Air store tent and keep it tidy. 3) Wait at table. 4) Light fire and keep it in all day, have boiling water for tea at 7.15 am.

Sanitary – Look after latrines, wash-houses, refuse pits, water pits, and incinerator. Keep camp tidy.

Messengers – Fetch milk morning and evening, fetch letters, collect letters and take to post, go any messages, fetch stores, etc., supply orderlies to the Guiders.

Orderlies – Carry water to kitchen and wash-houses, collect wood.

Mess Orderlies – Lay meals and wash up.”

For us viewing from modern times, it may seem like an awfully early start in the mornings, and a comparatively early bedtime, especially for the older Guides. The reason behind it was the need to match the day’s schedule to available daylight. With the only artificial lighting coming from candles, whether in candlesticks or glass-sided lanterns, the light available after dark was minimal and for emergency use only, hence it was necessary to be up early to get a full day of activity in before dusk, and bedtime was scheduled to get as much sleep in after dark as possible.

1933’s Campcraft advised:

“For any type of Guide camp an advance guard should arrive one or two days before the others to get things ready. The advance guard will probably consist of most of the camp staff (leaving one Guider to bring the Company) assisted if necessary by one or two Rangers or Patrol Leaders. The digging of latrines and the wash trenches should be done by a man two days before the camp opens. The screening for all this can be erected by the forerunners, the stools made and put up, the store tent pitched and all the stores put away in boxes and tins. If the Guides are coming to camp for the first time, the tents might be put up in readiness for them, but if they are old hands at the job, they might be left and each patrol can put up its own tent on arrival.” “When striking camp, if the work is properly organised it can all be done on one day, although a clearing-up party to be left behind is always popular.”

“No two camps are ever the same, therefore, every programme has to be adaptable. The main scheme can remain, but details will probably have to be altered at a moment’s notice, according to the fancies of the weather and the Court of Honour.”

“Company Camps:

6.45 – Cooks get up. 7.00 – Reveille. 8.00 – Breakfast. 8.30 – Orderly Work. 10.00 – Tent and personal inspection. Colours and Prayers. 10.30 – Cooks report at store tent. Gadget making, Singing, etc. 11.15 – Bathing parade, Station Signalling. 12.25 – Get ready for dinner. 12.30 – Dinner. 1.10 – Canteen. Court of Honour. 1.45 – Rest Hour. 2.45 – Free time, or bathing (if not in morning). 5.00 – High tea or picnic away from camp. 5.30 – Camp raiding, Woodcraft games, etc. 7.15 – Colours lowered. 7.45 – Supper. 8.00 – Camp Fire. 9.00 – Taps. Start to bed. 9.30 – All in bed. 9.40 – Silence Whistle.

Prayers and Colours might be held just before or directly after breakfast, and inspection of camp kit and tents could follow after the orderly work was done. Give something quiet after the bustle of orderly work, at which the Guides can sit down and relax. They are then ready for some good hefty work, or bathing, towards the end of the morning. The Court of Honour might meet at 9.45 am or at 9 pm. if preferred. In the case of the latter, the Leaders would be allowed a few minutes’ grace to get into bed. The Rest Hour must be a silent one. The camper wil nearly always go to sleep, but books, which can be borrowed out of the Camp Library, might be allowed to be read. Free time for letters, etc., is put after the rest hour to allow one to continue into the other and to prevent unnecessary rushing about. The expedition could be made to some place of interest, or if a nature competition is on foot, to allow the Guides an opportunity to get on with the work. If tea is being taken out the party will probably start about this time. Efforts should be made to get right away from the camp site every day, and to give the Guides the opportunity to see as much of the country as possible. The official hour for lowering Colours is just before sundown. If the entire camp is going out for an expedition, the Colours must be lowered, whatever time of day, before leaving the camp site, the idea of this being that there is no one to guard them. The “Camp Fire” may take the form of a genuine fire round which the campers may gather for songs and yarns. On a chilly night variations may be introduced in the form of country dancing, games or woodcraft competitions. If preferred, ‘Taps’ or ‘Lights Out’ or some goodnight song may be sung after the last whistle has been blown. It is the final signal for silence and often comes as a perfect end to a perfect day.”

“The Holiday Spirit. The great thing in planning all Guide camp programmes is to remember first that we are trying to show the Guides the wonders of the outside world, and secondly that it is to be above all things a real holiday. Leave all the Clubroom atmosphere behind and don’t mention the word test or badge till camp is over. Let the Court of Honour make suggestions about the programme and plans for the day, because it is through them that one can get at the general feeling of the camp.

The Patrol Spirit – The Patrol spirit can be kept up by means of charts, trophies or ribbons, which will record the daily progress of the Patrols. Points can be given for the tidiness of tent and person and good orderly-work, while others might be added for games, labour-saving devices, gadgets, etc. Mention might here be made on camp equipment, in camp and out of it. The official undress camp uniform of open-necked short-sleeved overall and camp hat or handkerchief to go over the head, in conjunction with sandshoes and no stockings, is extremely comfortable. The British public will, however, judge us by outward appearances, and we must give them no room to criticise. When going off the camp site, whether to Church Parade, for the milk or the post, full kit must be worn; and it’s only when the camp bounds are safely passed on the return journey that the irksome stockings and high collar and tie may be discarded.”

“Wet Weather – A wet day in camp need not be so wearying as is generally supposed! The cook place is kept moderately dry by an improvised shelter; the Colour is not put up, unless a small storm flag can be provided; prayers can be held in the barn, school, or other solid shelter, so necessary to complete the perfect camp site. A strict watch must be kept on tents and bedding. If there has been a wet night the latter must be thoroughly inspected and any which is damp or at all doubtful must be dried. The tent guy lines must be slackened, pegs knocked in, and if a strong wind is blowing the tent must be steadied on the windward side. Most of the children, except those who are unwell, or prone to rheumatism, may go out, rain or shine. Long coats or mackintoshes will hide the fact that skirts have been discarded; stockings in this case would not be worn and sandshoes are best to walk in. Guide hats are a good solid shelter for the head, if an iron can be borrowed to revive the brims before going home. Keep the children on the go all the time, and when back in camp again dry feet, shoes and stockings and a good hot meal will do away with any chance of cold. If the rain seems likely to continue the tents may have to be abandoned for the more solid shelter. Hardiness is one thing, but fool-hardiness is quite another. While in camp the Guider is responsible for the children under her care and it is no use risking too much for the sake of a little extra trouble.

Sundays – Sunday in camp is sometimes rather a problem. Anti-Guides have been heard to remark that camping tends to make us ‘godless gypsies’. It is well to know at times what the outside world thinks of us, but in this case one feels that the accusation is without foundation. The ordinary routine work of the camp will have to be done in any case, but it should be our effort to make the rest of the day so different, yet happy and jolly, that it will stand out by itself among the memories of camp. By past experience it has been found that there is a unanimous vote for a church Parade. This should be, of course, entirely optional. (See Rules 4 and 33.) A ‘Guides Own’ may be held as well as, or instead of, the Church Parade; if in the case of the former, after tea is a good hour.”

Orderly Work:

“Cooks – Rise at 6.45 pm. Half the patrol put on overcoats, light the kitchen fire and get the water on. The other half dress, and finish cooking the breakfast while the ‘early birds’ get dressed. 10.30 am – Report at the store tent. Cook the dinner. 4.15 pm – Half the patrol put on the water for tea and do any necessary cooking. 7.15 pm – Half the patrol warm up hot drinks. The cooks wash over the pots and pans and keep the kitchen tidy. They put on dixies, etc., after each meal is served to boil water for washing up.

Wood – Collect, saw and stack firewood. Keep the cooks supplied with wood, and keep the camp tidy. Bring out supplies from the store tent and food from the kitchen and extra utensils from the table. Wash up serving dishes and extra things which have been used. Lay the camp fire and light as required. Cover the wood stack at night and when it rains.

Sanitary – Sprinkle chloride of lime into latrine trench and cover it with earth to depth of two inches, twice a day if necessary. Scrub seats with disinfectant soap putting a little lysol into the water. Burn out latrine incinerator, and empty night latrine (if bucket) or fill in hole. Move seats up the trench when necessary. Be responsible for screening and roofing of latrine, adjusting when necessary. See that there is a plentiful supply of earth and paper in each cubicle. Dig fresh grease pits when necessary. Re-thatch lattice of grease pit every morning and burn up greasy leaves. Cover the day’s refuse with earth and ashes, 2 in. deep. Provide the Colour Party.

Water – Supply the cooks with water. If it has to be carried from some distance a big receptacle outside the wash tents should be kept filled, otherwise each Guide can fetch her own washing water. Fetch the milk from the farm once or twice daily. Post all letters. Prepare vegetables for the cooks between 8.30 and 10.00 am.”

“Many camps err on the side of being over strenuous. It is well to remember that the Guides are on their holiday, and we do not wish them to return home nervous wrecks. A good ten hours sleep will do them no harm after a tiring day in camp. It is always best to get them to bed in the light, the necessity for lanterns in the tents thus being avoided. It serves no useful purpose to let them get up too early in the morning when the dew is at its heaviest, 7.a.m. is quite early enough for Reveille. Remember also that Guides should be given plenty of time to have their meals in peace; rush ruins the digestion. Above all, the campers must be very strict about the Rest Hour. So many reasons why she should be excused from this are brought forward by the ingenious Guide. there is only one safe rule, i.e., never to listen to any of them. Any other portion of the programme may be set aside on occasion, but not this.”

Camp Catering

Guidance for quartermasters first appeared in the 1912 handbook. Equipment lists and menu suggestions were basic. For tent equipment: Bucket, lantern and candles, matches, mallet, tin basin, spade, axe, pick, hank of cord, flag, and pole-strap for hanging things on. For kitchen: saucepan or stewpot, fry-pan, kettle, gridiron, pot hooks, matches, bucket, butcher’s knife, ladle, cleaning rags, empty bottles for milk, bags for rusks, potatoes, etc. The tents were either ex-army bell tents, or hired ridge tents. For food, suggestions included ‘rusks’ – stale bread baked until hard, and tinned meat, beans, rice and porridge. Suggested rations per Guide per day were 2 1/2 oz oatmeal, rice or macaroni, 1/2 lb potatoes or 1 1/2 lb onions, 1/2 lb biscuits or rusks, 1/2 lb peas or haricots, 2 oz sugar, 1/4 lb fruit; or 1 1/2 oz jam or syrup, 1/2 oz tea or cocoa, 1/2 lb meat; or fish; or 1 1/2 oz cheese. 2 pints milk, 1 oz butter. Plus salt, pepper, currants, raisins, flour, suet, etc.

Quartermasters were also in charge of general equipment, so there were also hints on how to make a frame of sticks to put over a fire in order to dry wet clothes. Water might be drawn from a stream or pond, boiled if required. Cooking hints included making meat into “kabobs”, or wrapping it in either wet newspaper or clay before cooking it – or for poultry, heating a suitable stone on the fire until very hot then inserting it in the cavity so the bird cooks from the inside as well as being grilled on the outside on a spit over the fire. A “billy” or camp kettle could be either stood on the fire logs or among the hot embers of the fire for hot water, or supported by a lashed tripod of green sticks. Eggs, potatoes or buns could be cooked among the embers. Cooking was done on a trench fire, made of sods or logs, channeling the heat of the fire down the channel of the trench to make best advantage of the heat generated. Recipes were given for Hunter’s Stew, Bread-Bannocks, Pancakes, Dumplings, Beef Pudding, Bacon and Beans, and Rabbit Bish-Bash (made from a freshly caught rabbit, once skinned and cleaned out). Hence a lot of the cooking was based on either buying produce from the farmer or catching it for yourself, along with a certain amount of goods from the grocer and greengrocer.

In 1921 Guiding published ‘Notes on Camping’ which advised:

“Kitchen

1) Trench Fire and Oven. Dig a pit 2 ft. square and 2 ft. deep. From this dig a trench 1.ft. 6 in. deep, sloping up to 6 in., the width of a spade. Length according to the number of dixies required on at once. Put bars on the side of the trench to keep up the sods, and build up round the chimney 1 ft. high. The chimney should be from 2 ft. to 3 ft. high. A large tin may be built in at the chimney end to use as an oven; in which case try and get the flames on three sides of the oven and on top.

It is advisable to line the trench with flat stones, as this prevents the sides from burning away, and also makes the fire much hotter.

In case of wet weather always roof in your trench fire as follows: Have four upright poles and four roof poles. Put a tarpaulin on the top for a roof, and, if possible, another at the side to keep the wood dry.

2) Hay Hole. Make a hole in the ground according to the size of the pan (which must always have an overhead handle). Make the hole large enough to allow a lining of from 6 in to 9 in. of hay, straw, or newspaper. Fill a sack with same, and place on top, cover with sods. Use in the same manner as a hay box.

KITCHEN RULES

1) Cooks should wear clean and washable overclothing, and not make the meals appear unappetising for those who have seen the cooks.

2) Keep all kitchen things off the floor.

3) Baked sand or wood ash is the best thing to clean saucepans.

4) Store keeper is responsible for the ordering, keeping, and distribution of all food.

5) Cooks should be free from all other duties, and are responsible to the store keeper for everything.

6) Waste water should never be thrown on the surface, but into waste water pit.

7) All resuse excepting that for pigs must be burnt in the incinerator.

STORAGE OF FOOD

1) All food must be kept in a ridge tent, or improvised larder, and everything off the ground except tins.

2) Always have plenty of butter muslin.

3) Be careful over milk, and don’t keep it over night.

4) Never keep butter or milk near meat or anything strong smelling, as both are easily tainted.

5) Always hang meat, and keep covered from flies; don’t let the covering touch the meat. Make a frame with sticks.

6) Never keep meat over leaf mould.

7) Keep water cool and covered with muslin.

8) Larders can be made from packing cases, with holes back and front.

9) If near a stream or fast-flowing water float the milk cans in it, with the lids off or reversed.

10) To keep Milk fresh. Use 1 in 30 solution of medical bacterol in water. One tea spoon added to one gallon of milk as soon as it arrives in camp.

11) Air the store tent every day. Take everything out, brush the floor, and spray with Milton.

RULES FOR MEALS

1) Make the Guides orderly for meals, and allow no one to get up and wait except the orderlies.

2) Most important to have tables of some kind, and, if possible, benches to sit on.

3) Don’t let the second helpings start until everyone has finished their first helping.

4) If prayers and inspection are before breakfast, be sure that each Guide has had a biscuit or some bread and butter.

5) Have an inspection of all kitchen utensils from time to time.”

At this time cooking was invariable done as ‘Company cooking’ – one Patrol, supervised by the quartermaster, cooking all of the day’s meals, with a rota running through the week so each patrol took their turn.

As 1933’s ‘Campcraft’ advised “In camp life the dietist has a unique opportunity of teaching the children more healthy habits with regard to food and drink, and indeed, to instill into them the liking for foods which are sometimes unknown or distasteful to them. To take two instances, those of porridge and green salads.” And as it also warns “At one time or another most campers have seen the unedifying spectacle of burst flour bags, oatmeal converted prematurely into porridge on the wet grass, a pot of jam changed miraculously into a pot of wasps, butter into oil, and meat into maggots; also one has sampled various curious blendings of flavours, fortunately more or less peculiar to camp life, kippers and coffee and milk and paraffin”

Food can be stored in hanging larders and meat in meat safes; rivers can be utilised for keeping dairy products chilled.

For a camp oven, “Dig a square 18 in. by 3 in. deep, then finish off by adding four corner pieces sloping up to earth level. Place a brick at each corner and on these lay four iron bars or a slab of cement or some substance that will bear weight and stand heat. For the actual oven a large tea tin or four slabs of cement or sufficient bricks to form an oven 14 in. square. Any cracks likely to let smoke through can be filled in with clay. Pile sods up thickly around oven walls. For the top or ‘door’ use a removable slab of cement or iron or even a piece of weed and, to crown all, a large sod. The sods should be damped from time to time in case of any signs of crumbling with the heat. The fire is lighted underneath at the corner from which the wind is blowing, and it will be found that this arrangement allows much scope for the erection of dampers, flues, etc., and that long branches and pieces of wood can be used, thus economising in wood chopping labour. The meat or cakes should be placed on tiles or bricks to guard against excessive heat at the bottom of the oven. This oven retains its heat for a very long time, and long after the meat has been removed, cakes can be baked without adding fuel.”

“A camp boiler is a tremendous boon to all campers, and a serviceable one can be bought at any army stores for a very low price. It will hold 20 gallons or more. The zinc tank, iron fire basket and chimney are all separate and therefore easily transported. With a good fire the water will boil in ten minutes.”

“Menu for 30 Guides for one week at approximately 8/- per head.

Breakfast each day – Porridge, sugar, milk, tea, bread, margarine and jam. Tea each day – tea, bread, margarine, jam and buns.

Saturday – Dinner: Steak & Kidney pudding. Potatoes. Greens. Rice Pudding. Supper: Soup. Fruit Salad.

Sunday – Dinner: Hot Mutton. Potatoes. Greens. Pond Pudding. Supper: Savoury Jelly. Green Salad. Chocolate Mould.

Monday – Dinner: Cold Mutton. Potatoes. Lettuce. Treacle Pudding. Supper: Soup. Macaroni Cheese.

Tuesday – Dinner: Beef Stew. Dumplings. Potatoes. Stewed Plums. Supper: Boiled (or Scrambled) Eggs.

Wednesday – Fricasse. Rice. Vegetable. Apple Pudding. Supper: Cocoa. Biscuits. Cheese. Fruit Salad.

Thursday – Corned Beef. Potatoes. Salad. Raisin Pudding. Supper: Soup. Savoury Patties.

Friday – Herrings. Potatoes. Jam Pudding. Supper: Cocoa. Cheese. Biscuits. Tomatoes.

If thought advisable, an extra dish for breakfast could be given as follows: Saturday, Kippers; Sunday, fried bacon; Monday, eggs; Tuesday, cold ham; Wednesday, fish cakes; Thursday, cold ham; Friday, eggs. This would entail an extra charge of 1/3 per head for the week.

Budged ot above menu for a week in camp.

Meat – Leg of mutton (12 lb.) – 13/6. Stewing beef (7 lb.) – 8/0. Corned beef – 7/6. Steak and Kidney (5 lb.) – 6/6. Total £1 15/6.

Fish – 30 herrings – 5/0.

Milk – 7 quarts per day – £1 12/8.

Bread – 7 2lb. loaves per day – £1 1/0. Buns -17/6. Total £1 18/6.

3 lb. apples – 2/0. 1/2 cwt potatoes – 8/0. Cabbages – 1/6. Carrots, onions, parsley – 2/6. 4 lb. tomatoes – 2/6. oranges/bananas – 3/0. Lemons – 1/6. 4 lb plums – 2/6. Green salad – 2/0.

Tea (3 1/2 lb.) – 7/6. Margarine (10 lb.) – 6/10. 3 lb. cheese – 3/0. 3/4 lb. cocoa – 1/6. 3 dozen eggs – 7/6. 1/2 lb. coffee – 1/0. 12 lb. jam and marmalade – 12/0. 22 lb. flour – 4/8. Marmite – 2/6. Gelatine – 9d. 6 tins of fruit – 9/0. 2 lb. treacle – 1/4. 1 lb. lentils – 6d. Bar chocolate – 4d. 4 lb. rice – 1/0. 1 lb. lard – 10d. 12 lb. rolled oats – 3/0. 3 lb. macaroni – 2/6. 1 lb. raisins – 1/2. 2 lb. prunes – 2/0. 1 lb. currants – 1/0. 8 lb. sugar – 4/0. curry powder – 2d. Salt, pepper – 8d. Oil, vinegar – 2/0. Ixion biscuits @ 7d. per lb. – 17/6.

Total = £11 11/5.

Extra for breakfast: Ham (10 lbs.) – 18/0. Eggs (5 dozen) – 15/6. Fish – 3/6. Bacon – 4/6. Kippers – 4/6. Total = £2 6/0″

The book also includes recipes for the following at camp: White Soup, Stock, Macaroni Cheese, Indian Toast, Savoury Potato Cakes, Scrap Patties, Camp Fricasse or Curry, Savoury Jelly, Russian Salad, Sheep’s Head Brawn, Herrings, Cooks’ Farm Eggs, Fruit Salad, Treacle Pudding, Jam Pudding, Pond Pudding, Raisin Pudding, Date/Fig/Cocoanut Pudding, Doughnuts, Scones, Oatcakes, Egg/Cheese Savoury.

“The camp variety of hay box will be found most useful – all the usual arguments in its favour hold good, indeed on occasions it is almost indispensable and, at the worst, it makes a permanent and comfortable seat for the cook. Choose the dixie most suitable for the cooking of porridge, etc., and dig a hole 12 inches deep and 6 inches wider than the said dixie. Line the hole thickly with hay or straw, fill the dixie with water, boil up, put the lid on tightly and place in hole. Pack tightly all round with hay (or straw). Fill an old cushion cover or piece of sacking with hay and ram on top of the dixie. Then sit on the cushion and go to sleep. When you wake up and remove the cushion and the dixie a nice soft warm nest will be found. If possible always use the same size dixie in the hay box, as this will keep the walls solid and compact. Food that is to be cooked in the box must be started on the fire. Porridge should boil for 10 minutes, macaroni the same, stews should simmer for half an hour at least and potatoes for 10 minutes. Rice should boil for 5 minutes and beans for one hour. All food requires three times as long to cook in a Hay Box as it would on a fire. Therefore, porridge should be cooked overnight and if necessary warmed up for breakfast.”

Camp Sanitation

The 1912 Handbook gave advice on camp health and hygiene. As the handbook advised: “Many parents who have never had experience of camp life themselves look upon it with misgiving as likely to be too rough and risky for their girls; but when they see them return well set up and full of health and happiness outwardly, and morally improved in the points of practical helpfulness and comeradeship, they cannot fail to appreciate the good which comes from such an outing.”

Bathrooms were dealt with under the heading of ‘drains’ – “do not neglect to dig a long trench to serve as a latrine. Every camp, even if only for one night, should have a sewer trench two or three feet deep, quite narrow, not more than one foot wide, with screens of canvas or branches on all sides. Earth should always be thrown in after each use, and the trench must be filled up before leaving the place. Even away from camp a small pit should always be dug and filled in with earth after use.”

Water supply was generally drawn from a spring or stream using canvas buckets, with the water being filtered or boiled.

For rubbish disposal, the suggestion was to prepare two rubbish bins, one for threads, matches, paper, hair and general rubbish, the other for egg shells, banana skins, bones, etc – this rubbish could then be buried or burnt.

For camp beds, the recommendation was “to have some kind of covering over the ground between your body and the earth, especially after wet weather. Cut grass, or straw, or bracken are very good things to lay down thickly where you are going to lie, but if you cannot get any of these and are obliged to lie on the ground, do not forget before lying down to make a hole the size of a teacup in which your hip joint will rest when you are lying on your side; it makes all the difference for sleeping comfortably. If your blankets do not keep you sufficiently warm, put straw or bracken over yourselves, and newspapers, if you have them.” “To make a bed, cut four poles, two of seven feet, two of three feet – then lay them on the ground, so as to form the edges . . . cut four pegs, two feet long, and sharpen, drive them into the ground at the four corners to keep the poles in place. Cut down a fir tree, cut off all branches, and lay them overlapping each other like slates on a roof till a thick bed of them is made, the outside ones underlapping the poles. Cover with a blanket. It seems like a lot of work but it’s worth bearing in mind that in this era camps would often last a fortnight, some early accounts are of camps lasting a month!

At this time, battery torches weren’t common, so lighting was provided by candles. Suggestions were given for improvised candlesticks, made from bent wire, split cleft sticks, or a bottle with the closed end cut off using a hot string. These open flames in tents, naturally, involved a certain amount of fire risk, and is the reason why most camp timetables were based around rising shortly after dawn, and heading to bed whilst it was still dusk.

1921’s ‘Notes on Camping’, the official Guiding publication advised:

“1) How to Construct a Latrine. Dig a trench from 8 ft. to 4 ft. deep, 8 ft. wide at the top, and 2 ft. wide at the bottom. Long enough to accommodate 10 per cent. of the campers, allowing 3 ft. to each compartment. Pile the earth from trench behind, but leave room for the screening. Sugar boxes, about 2 ft. square, with oblong holes in the bottom, reversed on poles, make the best seats. Be sure to have the holes large enough, and no wood in front of the seats. Poles put across trench (not lengthways). Have latrines situated at least 60, and not more than 100 yards, from the camp.

If latrines are very far from the Camp, have a pail latrine in the centre of Camp for night use only. It must be removed before breakfast.

2) Pail Latrines – If the ground is too rocky for digging, these must be used. Put up screening in the same manner as for trench latrines.

3) Urinal Latrines. Dig a shallow trench 18 inches wide, leading into circular pit 1 1/2 ft. deep, and 3 ft. in diameter. Fill the pit with stone and bricks, not tins or bottles, as these might hold up any liquid. Allow 5 per cent. Trenches may be dug all round the pit if necessary.

SANITARY RULES

1) Tell Campers that neglect of personal sanitary discipline means expulsion from Camp.

2) For the safety of all, excreta must be covered with earth at once.

3) Sanitary Patrol must always be on duty.

4) Latrine seats must be scrubbed twice a day with lysoll and water.

5) A liquid form of disinfectant should not be used. Chloride of lime thrown down twice a day is best. Fill in all along the trench to 1 in. twice a day. N.B. This should be done by the Captain.

6) In each compartment there must be placed a box filled with earth fine enough to pass through an 1/2 inch sieve, and in each box a small trowel or tin for throwing earth into the trench.

7) Keep the sanitary paper in tins. If possible get round tins and make a small hole each end and a slit in one side; then pass a string through the holes at each end and through the roll of paper. The paper should then pull out through the slit in the side.

8) Always have a roof to your latrines, and provide each seat with a cover of American cloth attached to the back of seat.

9) Never use a latrine within 1 ft. of the top of the trench. Fill in and mark plainly with L for future campers.

10) Sanitary Patrol must always be on duty; they should not have anything to do with food on the same day as they do sanitary work.

11) Latrines must be situated to leeward of the Camp, in a down stream direction, and on ground sloping away from the camp.”

1921’s Notes on Camping also advised on Wash Houses:

“2) Wash Houses. – Dig a trench 18 in. wide and 1 ft. deep, leading into a shallow soakage pit 4 ft. square. Allow 4 ft. for each compartment, and have enough compartments to accommodate 8 per cent of the campers. Have one double-sized compartment for use as a bath-room. If making more than three wash houses, make them back to back, as this economises in both material and ground, and is equally convenient. In this case dig two parallel trenches 18 in wide, with 1 ft. between them (to allow for screening, and soil dug out of trenches), let the trenches join and flow into pit as before. If your wash houses are not situated on a natural slope, it will be necessary to dig the trench about 6 in. deeper at the pit end.

WASH HOUSE RULES

1) Have a table over the trench in each compartment, and let it be large enough to take sponges, etc.

2) Have a towel rail in each compartment.

3) Have a wooden footboard in front of each wash table.

4) Have a clothes peg or rail in each compartment.

5) Let the Guides make string bags to keep their sponges in.

N.B. – Soil is most injurious to both skin and ears, therefore be sure that there are foot boards, towel and clothes rails in each compartment, and that the Guides are using them. If possible, let each Patrol have their own wash house, and be responsible for keeping it clean and tidy.

3) Waste Water Pit. Have two biscuit tins, a large one and a small one. Cut a lip in the large one, and cover the bottom with stones. Make holes in the bottom of the small one, and place inside large tin. Fill small tin with bracken, & c. From the lip of the large tin cut a small channel 4 in. wide and 2 in. long, leading into a shallow pit 1 ft. square, from this dig another channel 6 ins. wide and 9 in. long, leading into a soakage pit 3 ft. square. Fill the small pit with bracken, leaves, etc., and in hot weather lay branches over the large pit. The bracken in both tin and pit must be burnt and replaced twice a day.

4) Refuse Pit. Make this large enough and deep enough to take all tins, etc. Disinfect with chloride of lime each day, and fill in 1 in. with dry soil. Burn out all tins in the incinerator before putting in refuse pit.

5) Beehive Incinerator. Make four air holes with bricks, tins, etc., and build up between these with soil and sods; on top of this place a grid of some kind – old bicycle wheel, iron bars, etc., anything fine enough and strong enough to hold up the rubbish. Then make a wall of sods on top of the grid to a height of 18 in., (from the grid). Put earth over the sods, and, if possible, mud, making the whole as round and tidy as possible. Have at least one of the air holes large enough to rake out the ashes.

Stone Incinerator. Hollow out a saucer, the deepest part being 18 in. Make a wall of sods and perch round the saucer to keep out rain and water. Line the inside of the saucer with stones. Build a cairn of large stones in the middle 2 ft. high. Must have something dry to start the fire with.

Brick Incinerator. Build in the same way as the beehive, only dig the air holes out to a depth of 18 in. in the middle. Make the wall 2 ft. high.”

One can’t help but think that all this excavation in his good grass fields must have been of some concern to the farmer or landowner . . . !

1933’s “Campcraft for Girl Guides” recommended that the latrine trench should be “three feet deep, one and a half feet wide, and six feet in length, for each cubicle. This sized trench will last for a week, an extra foot in depth will serve for a fortnight. Digging a trench for even a small camp is a very big job; it is therefore strongly advocated that a man be employed to do this, and to help with the erection of the screening.” The latrine screening would be of hessian or cheap quality sheeting, and “a thrifty Company will buy its screening, make it last from year to year, and so save the cost of hire. This is generally about sixpence per yard per week.”

As can be seen in the diagram on the right, at the start of the camp the toilet seats would be situated at one side of the cubicle, with the rest of the trench in each cubicle covered by boards, if the screening did not incorporate a fabric roof. Each cubicle would have, in the corner, a supply of earth dug from the trench and a trowel, so that after using the lat, each camper could ‘cover her tracks’ and leave a fresh trench with no sign of previous usage, ready for the next camper. Each morning, the toilet seat units would be moved along to the opposite side of each cubicle, and the boards switched round if boards were used – so that the trench would be filled in fairly evenly over the course of the week or fortnight. It was advised that any spare ashes from the kitchen fire should be added to the trench as a disinfectant, and Chloride of lime added to the trench daily. “A 3d. packet will generally be sufficient to ‘dress’ three cubicles. Remember that too much chloride is as bad as too little.”

Each cubicle would be provided with toilet paper, often stored in a tin with a slot which could be hung up from one of the poles to act as a dispenser, and with a vacant/engaged label or equivalent sign at the door, to avoid users being disturbed.

“Guiders always have a separate latrine, either near the one used by the girls or equally out of sight. If the Guides are of very mixed ages, it is advisable to apportion the latrines for the use of older and younger girls, according to numbers. As nothing in the shape of rubbish must be thrown down the trench, it is suggested that a portable incinerator be kept in the cubicles allocated to the older girls, as a receptacle for soiled towels. The incinerator can be made of a 7 lb biscuit tin, fitted with a moveable wire netting basket inside. This can be taken out and the contents set fire to, once or twice daily as necessary.”

“Suggested rules for Latrines. 1) Shovel plenty of earth into the trench after using. 2) No rubbish of any sort to be put down the trench. 3) Wash hands after using latrines. 4) Make use of latrines before bathing.”

Facilities within the cubicle often included a seat – despite “Campcraft” stating “It is entirely a matter of choice whether seats are used at all. I would, however, suggest that they are provided in a camp of novices, young or nervous children.” The alternative would be for the user to stand astride the trench, though one could understand some younger Guides especially, not having the same stride-length, would have concerns about falling down the trench.

One of the most popular seating options was the ‘sugar box’ – at that time, sugar was supplied to grocers in large sturdy wooden boxes. These were reckoned to be of an ideal size when upturned to make a latrine seat. The centre plank of the three forming the bottom of the box was removed, and some of the wood cut away in a semicircle from the boards at either side in order to widen the hole, then the top surface sanded smooth. A cover made of American cloth was attached to the upturned box, to prevent the seat becoming damp, or excess rainwater getting into the latrine trench during inclement weather (as improvised lat screening often did not have a roof). The box was mounted on a couple of spars, which stretched beyond the trench on either side to ensure the box was securely positioned over the trench and could not fall into it – a refinement was to add a ‘footboard’ at the front to help the user keep her feet (and her lowered garments) clear of the damp ground. Some commercial companies supplied folding stools which had a suitable hole in the seat, which could be positioned over trenches, although their shorter height could make them a less convenient perch than the sugar box option, and didn’t allow the addition of crossbar supports to allow for wider trenches.

Regarding wash tents, 1933’s Campcraft advised “If the campers are fortunate enough to get bathing, it must be made clear to them that this does not dispense with the use of the washing cubicles, nor may they make the daily swim an opportunity to use soap and a scrubbing brush! Washing accommodation may be provided either by curtained cubicles, tents, or some part of a barn or out-house. In every case, the minimum accommodation is one cubicle per patrol (more if possible), and one cubicle for the Guiders. Those who have camped with Guides, know how difficult it is to make then even take off their jumpers to wash, if there is a chance of anyone seeing them; therefore, for the sake of cleanliness it is necessary to make each cubicle or partition as private as possible.”

The design suggested was for cubicles of six foot square, with the two trenches ending in a shallow pit, 3 ft. square and 1 ft. deep. If the ground is sloping towards the pit the trench can be level, otherwise the trench should be sloped slightly towards the pit. “Each cubicle must be equipped with towel rail, small grid on which to stand, foot-bath, bucket, basins, and stand or rack for sponges, flannels, etc. These should not be allowed to be kept in the sponge bags or wrapped up in towels. The furniture used in a washhouse can be made by the Guides themselves on arriving in camp.”

“All campers have not the chance to bathe, but everyone should be able to stand a cold sponge down every morning. The pores of the skin, to be kept in healthy working order, must be cleansed daily from accumulations of dirt and sweat. This can be done best at night, when in most well-regulated camps, hot water is available. A cold sponge in the morning is of use more from a refreshing than a cleansing point of view. Patrol Leaders can be of great assistance in seeing that the Guides in their Patrols do not stint their ablutions. Special hints on hygiene may be given at the Court of Honour and the Leaders made responsible for seeing that they are carried out.”

“Garments worn next to the skin should be changed at the very outside twice a week in camp, and more often if possible. In cases where the organisation of the camp programme does not allow of sufficient time being given to the proper routine of a washing day, undergarments and stockings may be washed quite easily in cold water, and stockings may be washed quite easily in cold water, to which weak lysol has been added, with the help of a very little soap.”

In addition, refuse pits were dug (2 ft. square by 3 ft. deep) for rubbish which could not be burnt or put in the ‘pig pail’ for the farm animals. Incinerators were set up on turfed ground, a grease pit ((about 3 ft. square and 18 ins. deep), and a waste water pit.

“General Hints of Camp Sanitation. 1) Everyone is responsible for the tidiness of the camp; not only the Patrol on duty. 2) All dirty and greasy water to be emptied into its proper place. 3) Look after screening and guy lines of the latrines and washhouse. 4) Shots at the incinerator generally miss!

Duties of the Sanitary Patrol. Sprinkle chloride of lime into latrine trench and cover it with earth to depth of two inches, twice a day if necessary. Scrub seats with disinfectant soap putting a little lysol in the water. Burn out latrine incinerator, and empty night latrine (if bucket) or fill in hole. Move seats up the trench when necessary. Be responsible for screening and roofing of latrine, adjusting when necessary. See that there is a plentiful supply of earth and paper in each cubicle. Dig fresh grease pits when necessary. Re-thatch lattice of grease pit every morning and burn up greasy leaves. Burn out incinerator and old tins; hammer the latter flat and put in refuse pit. Cover the day’s refuse with earth and ashes, 2 in. deep. Scrubbing the stools seems to come at an awkward time in the morning; arrangements might be made to scrub them after dinner when ‘traffic’ is less heavy.”

“A careful Captain will find out before she starts for camp whether the heads of the Guides intending to go to camp are clean. If there is any doubt a special inspection should take place. An outsider, more especially a trained nurse, will often undertake this duty.”

Camping ‘Mod Cons’

In the 1912 handbook our founder, Agnes Baden-Powell, emphasised that Guides did not go to camp to ‘rough it’ – no, they knew umpteen little tricks and dodges to make camp life comfortable. Thus from the start, the aim of camping was to master the art of making yourself comfortable at camp, so that it was enjoyable, and there was every encouragement to seek the ‘mod cons’ which would allow you to do so. Although it was regularly made clear that making them was preferable to buying, it didn’t stop manufacturers providing a range of options for the wealthy camper who could be tempted to invest. Here we will look at the different types of ‘mod con’ which were available in each era, and for each area of comfort.

Tents

The first Guide camps used the same sort of kit that all early campers used at the start of the twentieth century – ‘army surplus’. Pre-20th century, the army were the main people to use tents, and as such they had developed the technology and camping techniques which civilians used and in time developed. Following the Boer War which had ended only a few years before, there was surplus army kit to be had, and it was possible to hire tents, catering size cookwear and the like, at modest cost. Hence, the first tents used for Guide camps were ex-army ‘bell tents’, being the only sort readily available from hirers, given camping was not yet a commonplace pastime. There were some clear advantages to them – each Guide had a share of luggage space available to her, they were comparatively straightforward to pitch, spares were readily available, and they could be pitched by a Patrol of Guides unaided. On the downside, ventilation was limited, the poles were very heavy to transport, and the centre poll had to be set up securely to avoid accidents. The average weight of a bell tent was approaching 80 lbs, whereas a good ridge tent weighed only half that.

For Guiders, the recommendation was a smaller ridge tent – bells were ideal for 6 or 7 Guides, but too large and draughty for only 2-3 Guiders. These ridge tents were of canvas, with wooden poles, but the poles were much more slender than on the large bell tents, and the overall design more compact. They allowed enough space for camp beds, and also for some of the activity equipment which all Leaders end up taking to camp – it’s never just their own clothing and bedding they have to bring!

As well as sleeping tents, so a storage tent was also needed, to store the equipment – food and cleaning materials, to store the activity equipment – sports gear, wet weather activities, nature reference books, books for the ‘Guides’ Own’ sessions, safe storage for the flag when not on the flagpole, for the toolbox, including the axes, saws, spades – and all the other items needed to equip a camp for all eventualities. These too were originally army surplus tents, known as marquees. They came in a range of sizes – for 15-20 Guides a marquee of 18 x 12 ft was recommended, for 20-30 Guides, 32 ft x 16 ft, and for 50 Guides, 40 ft x 20 ft. Strict warnings were given that they were not to be used as sleeping quarters.

In 1930, a week-long major gathering was held in Iceland, to mark the anniversary of their parliament. Accommodation was provided for all those attending in hundreds of specially-made canvas tents, ordered from ‘Blacks of Greenock’ in Scotland, and only used for that week. After the event, Blacks sold off these ‘second-hand’ tents at a very modest price – and Guide Companies and Scout Troops across the UK snapped them up, and on finding they were good, such was the demand for them that it led the company to make more – and they’re still making them now, 90 years on. Thus, the ‘Icelandic’ tent became commonly used UK-wide – and is still used by many units to this day. It is straightforward to pitch, has excellent ventilation, lasts for decades with reasonable maintenance, and as such, along with it’s close relatives the Stormhaven and Nijer, is often seen as the classic Patrol tent.

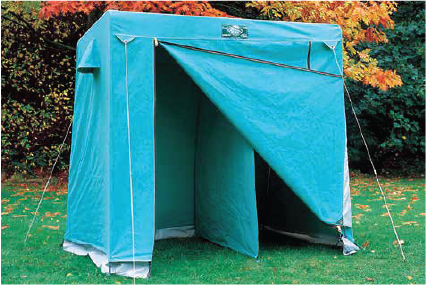

Tent technology remained broadly unchanged until the 1970s, when heavy wooden poles began to be replaced with tubular aluminium as the family ‘frame tent’ developed. This, together with progress in other materials, meant that tents started to appear which often had the poles linked together on the insides with metal springs. Although initially made of heavy canvas, soon lighter grades of cotton or nylon were being used which, along with waterproofing solutions such as ‘fabsil’, allowed fabric to combine lighter weight without loss of waterproofing. For store tents, another advance was the plastic window, which allowed light into the tent, and increased visibility for identifying the contents. These tents also tended to feature zip doorways rather than the old fabric ties, which were a little more bugproof and secure. One downside to the progress in terms of lightweight tents came where strong winds were concerned – in the absence of solid wooden poles and heavy canvas, and with their blocky shape and front canopy, any head-on winds meant relying on the quality of the pegging out as to whether the tent survived a gale or not!

The 1990s and into the 2000s saw some units swap their Icelandic tents for lightweight ones, as the options available in catalogues increased. The advent of carbon-fibre poles strung together on elastic, and modern synthetic waterproof nylon fabrics, made it possible to manufacture large tents which were significantly lighter in weight than the aluminium-pole options. Advances such as separate ‘pod’ bedroom compartments and built-in groundsheets made for increased comfort and privacy for the individual – but splitting the Patrols into little ‘chummeries’ had both pros and cons. They were cheaper to buy than the Icelandics, but tended to be much less durable, especially if Guides were careless over not tugging at zips, not protecting the groundsheets, etc. They also had a larger ‘footprint’, so weren’t so good on compact campsites, as they didn’t fit easily alongside each other in limited space.

Lighting

In 1912, the option was candles – and with the obvious safety risks of ‘naked flames’ in fabric tents, suggestions were made for imrpovised candlesticks and lamps to offer some degree of stability. These could be made by using hot string to cut the bottom off of glass bottles, by using forked sticks, or by buying commercially available lamps with glass lenses. Whilst applauding the desire for homemade, I think I’d have opted for the latter on safety grounds.

One impact of the limited lighting available from candles, is clearly shown in camp timetables. Candles give poor light, so camp timetables were arranged around utilising the daylight – hence the day starting soon after dawn with 6am starts not unknown – and everyone being in bed before dark, with lights out sometimes being as early as 9pm.

Later, battery torches became available, and this allowed more scope for camp activity after dark. Gas lanterns, too, became available and were increasingly popular for lighting marquees and other large areas, with torches tending to be for personal use. By the 1990s, the ‘head torch’ on an elastic strap was starting to become available – this was a real boon as it allowed the camper to use both hands for tasks, without the difficulty of also trying to wedge a torch underarm or between the knees and still point it at somewhere approaching the direction wanted!

Now, some unit camps use generators and other options to power lights, but most still use battery torches by night, with the occasional camping gas lantern.

Beds

From the early days, the bedding options for Guides, and for Guiders, differed. Altough the ‘camp loom’ to weave grass into mattresses was advocated, I’m not sure of the practicalities. On the first day arriving at camp, it would take a lot of work to install the stakes firmly, fasten the strings around the stakes, gather enough foliage to weave a mattress, and do the weaving – with the need to cut and fasten off the strings after each mattress was made, and then re-string it to make the next one – even if the camp were only 6-12 Guides it would take several Guides to collect the foliage and at least two to do the weaving – and thus several hours to make mattresses for everyone. And that alongside pitching tents and setting up kitchen and bathroom facilities. So although it’s good to record, and I have heard of instances of looms being made during camp as an optional activity, I doubt they were in widespread usage at any other than small camps of long enough duration to justify it.

Instead, more common was the ‘palliasse’ – a cloth bag made from cotton or hessian, which was taken to camp empty, and stuffed with straw on arrival – the straw being provided by the farmer. The art lay in the right quantity of filling – too little and you could find yourself lying on the hard ground with what little padding you had added surrounding you instead of being under you. Too much filling and you were inclined to perch on top and end up rolling off the edge onto the hard ground. In either case, on top of the palliasse you would arrange your blankets before securing them into a rectangular bag shape using ‘blanket pins’ – similar to nappy pins or kilt pins. The strong message was ‘as many layers of blanket below as above’. In some units, the palliasse cases were made by each camper, but in other areas hiring them seems to have been the norm.

Meantime, for Guiders who cared to invest, there was the option of taking a folding camp bed, obtained from army surplus. With their sturdy wooden frames, they were heavy to transport, and with no insulation below other than the canvas base, several blankets were needed to achieve warmth. But Guiders in those days tended to be wealthy, and soon there was the option of a down-filled ‘sleeping bag’, which would have been a practical and comfortable option.

Another option became available for Guiders with the advent of the ‘air bed’ – blown up using a foot pump, these were usually made of thick rubber which was coated with fabric. More compact than a folding camp bed, and taking up less space in the tent due to being nearer the ground, nevertheless they weren’t necessarily any lighter – the thick rubber had a fair bit of weight to it too. It was also warmer than the camp bed, as there wasn’t the space underneath the bed for draughts – but the air bed itself didn’t contribute warmth, so comfort still relied on the quality and extent of the bedding put on top of it.

It was post World War II before the average Guide was able to move from blankets held together with blanket pins to having manufactured sleeping bags. At this stage, these were still rectangular. And by this time the palliasses were gone, so Guides were spreading their blanket-wrapped sleeping bag on a groundsheet, with no other padding. But the sleeping bags remained a rectangular shape until the late 1970s, when the first shaped ‘mummy’ sleeping bags were introduced, shaped to fit the body snuggly. In the 1970s wool blankets became rarer – more houses moved from having sheets and blankets to fitting their beds with ‘continental quilts’, and then later with ‘downies’, rather than the old-fashioned blankets and bedspreads, which made laundry easier. It meant that for camping, the blankets which were wrapped around the sleeping bag were often replaced by a checked wool ‘travel rug’, which was lighter to carry, but also not quite so warm as a thick wool blanket would have been.

In modern times, camp bedding tends to have many more components. To ease the back, a compressed foam mat is a common choice, offering good padding whilst being lightweight. For Guiders, a self-inflating mattress is popular – a bit more heavy and bulky, but with it being thicker it offers greater comfort, with more padding between the body and the hard ground. The basic nylon sleeping bags of old have been replaced by different grades of sleeping bag for different temperatures – the level indicated by how many ‘seasons’ it is considered appropriate for. The old wool blankets are now very hard to come by, and even the 1970s-style wool ‘travel rug’ is becoming rare – so in modern times ‘fleece’ blankets are used, which are lighter but are also not quite so warm as the travel rug. Where traditional tents such as the Icelandic are used, the bedding is still rolled up and wrapped in the groundsheet to form a ‘bedding roll’, but where lightweight tents are used, some units opt to utilise a zipped plastic ‘laundry bag’ instead. Either way, keeping the bedding sealed up against the damp during the day remains the priority.

Toilets

During the first 50 or so years of Guide camping, toilets were very basic – a trench was dug in the ground, a pole inserted to hang on to, and using it to help you balance, you positioned yourself in a squatting position astride the trench to ‘do your business’. Thereafter, one hauled oneself back into a standing position, dressed, used the trowel to shovel some of the earth from the trench back into it sufficient to ‘cover one’s tracks’ and leave the trench ready for the next user. Screening was arranged around the trench – either barriers of woven branches or hessian fabric attached to stakes – and the site chosen was often behind a hedge if possible. At the end of the camp the trench was filled in and the turfs returned, and a marker with a clear ‘L’ left on the site to indicate the latrine’s location so that the ground would be left undisturbed long enough for natural composting to take place.