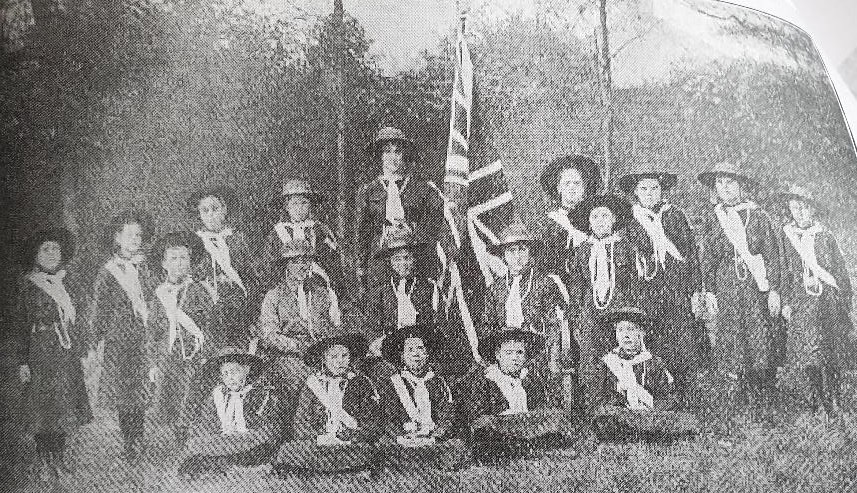

So, Girl Scouts existed and were recognised from the earliest days of Scouting in 1908, with Baden-Powell soon declaring in his personal column in “The Scout” magazine in January 1909 that some had proved themselves “really capable Scouts”. And although a few of those Girl Scouts may have become members by slightly devious means (such as filling in their initials rather than giving their obviously-feminine forenames on registration forms), the vast majority had registered openly with full and clearly-feminine sounding names – and were nevertheless welcomed as the enthusiastic and capable Scouts they were, regardless of their gender. Indeed, in some cases they had an official welcome, as was the case with one girl who wrote to Robert Baden-Powell and received an enthusiastic handwritten personal reply from him in 1908, on Scout headquarters headed paper. Naturally, those early Girl Scouts followed the Scout programme as nearly as they could given their circumstances – they met as Girl Scout Patrols, and worked together in their Patrols on challenges and badges.

Some were permitted to attend local Scout meetings with the boys, but most were not – for instance, the Cuckoo Patrol of Girl Scouts were attached to 1st Glasgow Scout Troop, but they met separately in a hayloft rather than attend the Troop’s regular Parades, and the Scoutmaster would visit the Patrol at their Patrol Den from time to time in order to pass them for their tests there, not at the Troop meetings. Uniforms worn by those early Girl Scouts initially tended to be variations on the suggestions in “Scouting for Boys” with many girls dyeing their brothers’ old cricket shirts and making uniforms from their old clothes or fabric they acquired – not exactly a problem in an era when all girls learned hand-sewing and dressmaking anyway – and these shirts were then teamed with the sturdiest of their long skirts. But by 1909 things became a little more straightforward in that regard – for in that year’s new edition of “Scouting for Boys” there were uniform guidelines for Girl Scouts – so there is no question that Girl Scouts were merely known about, or tolerated, but it’s clear they were actively being incorporated into Scouting as equals of the Boy Scout members.

The requirement for Patrol Leaders to have a decorated Patrol flag on their staff wasn’t exactly a difficulty for the girls either, when it would just be another piece of decorative painting or needlework amongst many they would do at home – indeed it’s quite likely that they offered the boys assistance with how to make their Patrol Flags too!

Due to some combination of the growing number of Girl Scouts, and occasional negative publicity emerging over the existence of mixed Troops, mixed activities, or mixed public rallies, at Robert Baden-Powell’s request the separate organisation of the Girl Guides was started early in 1910 by his sister, Agnes Baden-Powell – and most of the existing Girl Scout Patrols and units obeyed the order to transfer to being Guides (however reluctantly), as the Guide Law required them to obey cheerfully. Thus all soon went from being Girl Scouts to being Girl Guides, with the registration of Girl Guide Companies beginning in July 1910.

Initially, the only new information available on how Guides should be organised and run was in two pamphlets, later known as ‘Pamphlet A’ and ‘Pamphlet B’, and the ‘Scheme for Girl Guides’ published in the November 1909 edition of the Scout Headquarters Gazette, so meantime most units continued to follow the advice to adapt and follow the instructions in ‘Scouting for Boys’, and use their own judgement of how best to manage things – in 1911 the 5 Edinburgh Guide Companies paraded for a Royal visit, and it was found that although the actual uniform garments they wore were similar in basic style, of the five city Guide Companies present, one Company wore brown uniforms, two wore blue, one wore green and one wore bright scarlet!

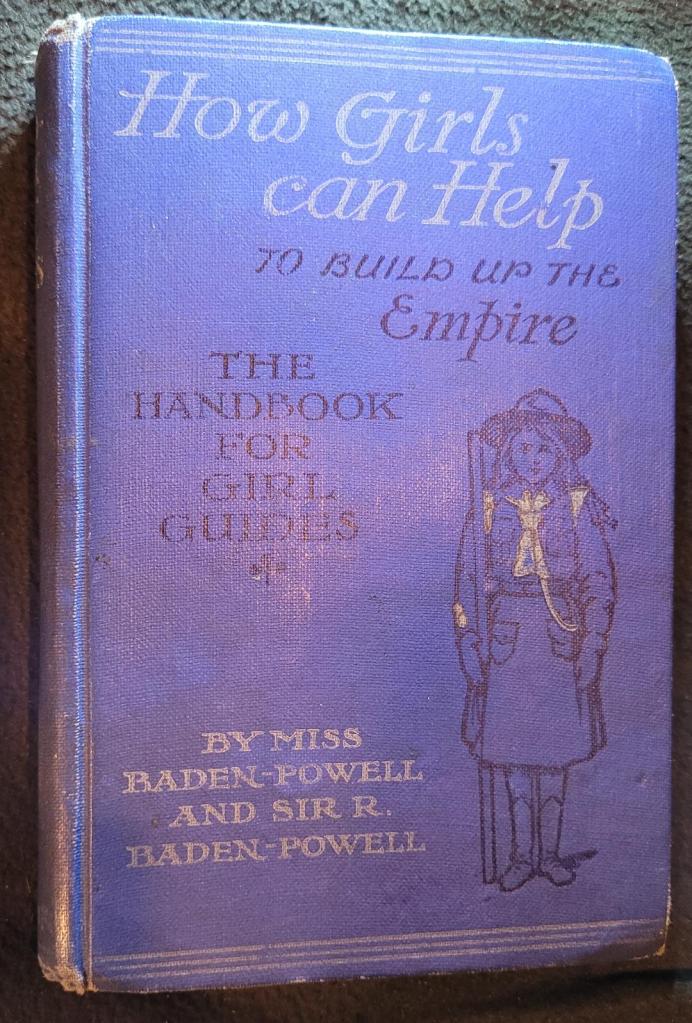

In 1912 the first Guide handbook was introduced, written by the founder of Guiding, Agnes Baden-Powell. She had adapted it from her brother’s book ‘Scouting for Boys’, and it still contained virtually all of the adventurous games and activities from that book which the early Girl Scouts had so much enjoyed tackling in their Scout Patrols. But – they were rewritten simply in order to coat them with a very fine veneer of femininity, in order to appease parents and other nervous adults who worried that the new scheme might lead their daughters astray, presenting it as a handbook for girls who might someday have to live in the farthest-flung parts of the British empire, where self sufficiency would be required of them in the absence of the ready access to the types of servants, doctors, or other trained help they were accustomed to in the UK.

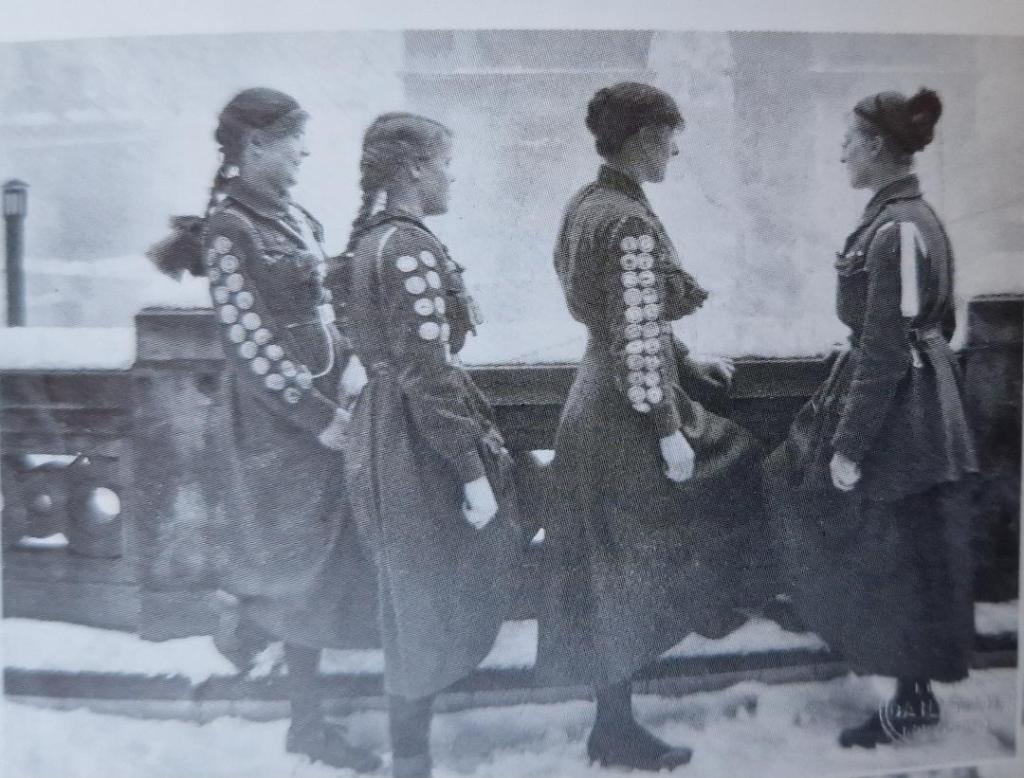

The handbook helped to clarify procedures and rules for units, where before people had had to judge for themselves how best to adapt the Scouting guidelines – and it helped to bring some regularity to uniforms and practices, albeit many girls still wore homemade outfits, particularly in areas where official uniform was not affordable or not readily obtainable – and some Patrol Leader chevrons and accoutrements were still extremely large and showy, tending to negate the oft-repeated assurances that the Guides were not militaristic!

It took time for Guiding to be accepted by the public – in the early days there were regular reports of parading Guides being jeered in the street, sometimes even pelted with mud or vegetables by little boys, hence the clear discouragement of Guide public parades – but we have to bear in mind that this was in the particularly militant stage of the suffragette era, when women’s rights and roles were a topic of very controversial national debate anyway – and Guides could inadvertently be seen as part of this general suffrage movement which sought greater rights and freedoms for girls and women, including the right to vote in elections, by a range of means, some of them illegal. It was doubtless this that the Duke of Devonshire was referring to when he said upon opening a girls’ school gymnasium that ‘he hoped that the gymnastic training given in the school would not induce any of the students to take part in the various movements which were better confined to the male sex. As a strong opponent of the Girls’ Scout movement, he trusted that the gymnastics would not induce them to take part in demonstrations of force at Westminster or elsewhere’. It has also been suggested that some adults feared that the girls were being prepared for war service as military nurses or the like, which the drilling and parades, and the extensive first aid training, might have risked suggesting. 1912 saw the first national subscription fee, of 3d per person per annum, in order to help defray the expenses of running the movement.

It was really with the coming of World War I that attitudes started to change regarding the capabilities of women in society in general, and of Guides in particular – the war offered the Guides a real chance to show the practical value of the training they had received, and the skills which they had practiced over the preceding four years in their units – and they certainly took it!

Guides were involved in acting as messengers, working in hospitals and teaching in nurseries, collecting waste paper, jam jars and bones, making and laundering hospital dressings, and many other important roles. Some worked as messengers at MI5 headquarters, carrying secret messages both in writing and by memory – they had shown that they were reliable and could be trusted. Many were involved in fundraising for causes such as the Red Cross and refugee funds, and they also had a special Guide fundraising drive, which raised enough money to set up and run an extensive and regularly-expanded rest hut for soldiers ‘behind the lines’ in France, and also to provide a ‘motor ambulance’.

Others were involved in gardening and farm work, to produce food for the country at a time when the combination of the sinking of cargo ships in the Atlantic and disruption to agriculture in the UK, brought Britain within weeks of full starvation, in spite of the food rationing which had been applied towards the end of the war.

At the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, older Guides acted as messengers to the British delegation, working throughout the Palace during the tricky negotiations, fully trusted to keep anything they overheard confidential, and to lay aside any national interest in carrying out their work. They had been recruited from amongst the Guides who had worked as confidential messengers for the security services (the forerunners of MI5) during the World War, because of the standards of reliability and dependability they had shown.

By the 1920s the uniform had stabilised as a navy overblouse (which is referred to in catalogues and reference books, confusingly, as a ‘jumper’) and long skirt, or a full-length dress, with twin chest pockets. This was worn with a cotton tie in the company’s colour, formed from a folded triangle, and a broad-brimmed hat with embroidered hat ribbon. Service Stars were worn on the flap above the left chest pocket – these were ongoing from Brownies, so that those gained as a Brownie had brown felt discs at the back, and those as a Guide had green discs. The Patrol badge was worn above the left pocket, and the belt was of brown leather. The uniform was worn with black wool stockings, and black shoes. Interest badges in this era were made of a felt-type fabric, which meant that they had to be removed from the uniform for laundry, and sewn back on the uniform afterwards – many blanket-stitched around the edge to reinforce the badges too.

Guiding now had public support in communities of all classes, and was rapidly becoming an accepted and ordinary part of national life. Just as in wider society, women had shown their capability, so the work which the Guides had done was increasingly recognised by the public. And as attitudes to what was appropriate for girls and women shifted, so it was possible for more Guides to go to camp – where pre-war it had been suggested that camping in tents could be dangerous to girls’ health, and many early Guides stayed in the shelter of farm barns rather than ‘risk’ camping in tents, by the 1920s it was recognised that camping in tents was a perfectly safe and healthy activity for girls, and it gradually became widespread.

Guides continued to work through their challenges – Tenderfoot, Second Class and First Class – and some managed to earn Gold Cords. It was not uncommon to see Guides parading in towns with their flags – the Union Flag, and the navy Company Colours featuring the First Class badge and the unit name, later replaced by lettered World Flags with brass Trefoils and long blue and gold tassels. Guiding expanded outwith the cities into many rural towns and villages, with new Guide Companies opening at a rapid rate – possibly linked to the rapid increase in the number of single young ladies and childless widows unexpectedly available and with the free time to become Guiders, an indirect and unfortunate consequence of the massive loss of young soldiers and officers in World War 1.

Interest badges were now widely available, and the original blue designs on white felt were soon replaced by the more familiar olive green, on navy felt. They still had to be removed from the uniform before every laundry, though, hence many of those in photographs appearing to be loosely tacked on in the middle rather than securely stitched around the edges!

In those areas where Guide Companies weren’t viable, and to cater for those who couldn’t realistically attend units, such as those living in remote locations or attending boarding schools which did not have school Companies, Lone Guides were introduced. The Guide meeting came in the form of a letter, sent on from Guide to Guide in the Patrol, containing news and challenges. Each Guide receiving the letter would carry out the activities and add in a note of the results, then send it on to the next Guide, with the last one in the Patrol returning it to the Lone Patrol Leader or Guider for assessment. Lones had a special Promise badge, with a large L in the middle, in blue enamel for the Guide section, and red for Rangers. Lone Guides continue to exist across the UK today (and especially in rural Scotland), often helped by internet links.

Special Guide units were also set up to cater specifically for girls with disabilities, in what was then called the Extension Section – because it saw Guiding extended into children’s hospitals and residential homes for the blind, deaf, disabled, and those with learning difficulties – at a time when many children with disabilities or major illnesses stayed in special boarding schools or on long-term hospital wards for months or years at a time with limited family contact. From a few pioneering units, soon a network of Extension units were established. Those in hospitals and residential schools adopted Guiding as an activity which allowed the girls whose lives were so restricted, have an opportunity for once to do just as other girls did, as far as possible following the same programme and tackling the same challenges. There were also Post Guides, who worked to link together physically disabled housebound girls into lone-style Extension units who received their meetings in the form of letters filled with illustrations and activities to try – especially important at a time when any children who weren’t able to attend the local mainstream school unaided received no formal schooling at all, and thus had little to occupy their days. Local Guide units were encouraged to ‘adopt’ any local Extension Guides living in their patch and visit them – sadly this idea was not always successful.

The Extension Promise Badge had lilac enamel, and some special early interest badges were made for extensions with lilac borders rather than green, with lilac later replaced by blue. It was regularly noted that the standard demanded for the Extension Handicraft proficiency badge was often higher than for the ordinary Guide Craft badge.

Nowadays most disabled girls are integrated into local units and follow the same programme as everyone else, and as there are only a few special units, usually based at hospitals or boarding schools for the blind or deaf, so they no longer have a separate Promise badge or challenges, and then and now alike, they tackle the same programme as every other unit does.

International opportunities, too, became available to those with the means, with International camps and other gatherings. The international Guide House, Our Chalet, opened in 1932 thanks to the generosity of Mrs Helen Storrow who provided the funding. It offered a welcome to Guides from around the world, and opportunities for Guides from different countries to meet and get to know each other, at a time when international travel was not so common as nowadays, and tended to take far longer.

But gradually through the 1930s, the political shadows were gathering across Europe, and especially so from the autumn of 1938, when the threat of war came so close, and was then seemingly so narrowly averted. Although the international Pax Ting Camp in Hungary went ahead as scheduled in August 1939, with representatives from many of the countries which Guiding had reached managing to send delegations as planned, some groups opted to alter the membership of their parties at the last minute, to ensure all participants were older Guides or Rangers who would have the skill and experience to evade capture and escape home overland in secret, should the worst happen and war break out whilst the camp was being held.

Fortunately, the peace held out, and everyone managed to get home safely – but within weeks war had broken out between Britain, France and their allies against Germany and hers, and engulfed most of Europe and many countries beyond. Sadly, the Guides of the UK were again to have an ideal opportunity to prove the value of their training, in adaptability, keeping calm under difficult conditions, first aid, rescue work, maintenance of morale, messenger work, salvage collection and many more . . .

Yet, even before war began, Guides in the UK had already been hard at work on preparations and precautions in case of war, especially stepping this up from the autumn of 1938 onwards, when the threat seemed especially strong and war seemed imminent – helping to assemble gas-masks and deliver government notices, with some older Guides undertaking specialist extra training in first aid and ARP skills. On the day war broke out, Guides were involved in meeting evacuees at train stations and escorting them to village halls, in preparing and issuing refreshments, in cleaning and preparing houses for evacuees, and in teaching town-bred children about unfamiliar country customs and ways – many urban children had never seen live farm animals first-hand. Many Guides raised funds for the red cross, helped at hospitals, served as casualties for first-aid practices, made clothing for the forces, trained to deal with incendiary bombs, and refurbished old toys to supply Christmas presents to poorer children who would otherwise receive nothing.

Evacuation during that first weekend of war meant that country Companies which had for so long struggled to muster enough girls to keep two Patrols going could overnight find themselves with 50 or 60 all wanting to transfer in – just as many of their Guiders had been called up for war service and transferred far from home and their units. Equally, large Companies in towns and cities found themselves suddenly reduced to just a few older Patrol Leaders who were of working age, as most of those who were under 14 were evacuated to the country with their schools. Many units were run by their PLs throughout the war in the absence of Guiders, and if some failed, many succeeded amazingly well.

Soon the Guides were teaching the authorities how to do ‘blitz cooking’ on improvised fireplaces made from bricks and scrap metal, helping with ‘after raid’ rescue squads to rescue people’s possessions from their bomb-damaged houses, and running canteens and rest centres in public air-raid shelters and halls, and also in mobile vans which travelled to recently bombed areas to feed those who had been bombed out of their homes, and the rescue workers serving there too. Country units were involved in picking hedgerow fruits and herbs for medicine, and working as labourers on farms during weekends and school holidays.

Later in the war, a new cause for fundraising began, with the start of fundraising for the Guide International Service. It was decided that teams of young Guiders should train up so as to be ready to go to Europe to work with refugees as soon as war ended – to ‘win the peace’ as it was termed – and it was clear that funds would be needed, both for the equipment to set up and run the hospitals and feeding centres the teams would create and operate in the recently-liberated areas, and also to cover the basic living expenses of the teams of volunteer Guiders who would go to staff them – so the GIS fund was born, and the Guides continued to fund the team from 1944 right through to 1950 and beyond.

Initially, camping in wartime was totally banned, but soon, subject to certain rules, limited camping was permitted. It wasn’t allowed near the coast, tents had to be camouflaged with paint or nets and located under trees, and camps couldn’t be far from home (although that wasn’t a hardship as petrol rationing and Government discouragement of unnecessary train journeys meant units couldn’t go far anyway!) In those ‘dig for victory’ days, many units went ‘farmping’ – camping on farmland in order to spend part of the time helping the farmer with farm and harvest work. Food rationing brough a further complication to camp menus with the need to juggle the rations and coupons – and that continued to be the case until the mid-1950s, but enthusiasm overcame all difficulties.

The end of the war brought new uniforms for Guides – the new ‘headquarters blue’ colour had been introduced in 1939 but transition took time due to the war – so with the war ending it was finally out with navy, and in with ‘headquarters blue’, – but programmes were little changed. New challenges were introduced, including the ‘Queen’s Guide’ award, and international gatherings increased.

With an international folk dance competition in 1947 and Empire Ranger Week in 1948, Guiding was busy with post-war events.

There were the Coronation celebrations in 1953 (especially valued since the new Queen had been a Guide and Sea Ranger), with units submitting their own tributes in the form of good turns.

Major celebrations followed, marking Robert Baden-Powell’s centenary in 1957, which included a special ‘centenary camp’ in Windsor Great Park. The role of ‘Company Leader’ was brought in, where a Senior Guide received a third stripe, worn diagonally across her existing stripes, and left her Patrol to become a sort of ‘PL to the PLs’.

And of course, celebrating didn’t stop, with 1960 bringing Guiding’s 50th birthday, and jubilee celebrations. Many pageants and gatherings were held, to mark the special occasion, and a special song was written.

The 1960s was also a time of looking ahead, with proposals for programme change being considered, culminating in the publication of the working party’s report looking at change for all the Guiding sections, which was titled, ‘Tomorrow’s Guide’.

The next big change was in 1968 when these changes were implemented, with a tweaked Guide uniform and new programme. The Second and First Class challenges were dropped, to be replaced with a series of ‘trefoils’ – yellow, green, red and blue (in that order). Patrol Leader stripes on the pocket were replaced by a smaller curved set of stripes to fit under the Patrol badge, and the Company Leader role was dropped. Set challenges were dropped and replaced by challenges chosen specifically for the individual by the Patrol Leaders’ Council. Many units now travelled abroad, both to international camps, and on holiday trips, with others travelling further afield within the UK. The high birth rate meant increasing numbers of Guides, with many new units opening up.

1970 brought diamond jubilee celebrations, with special international camps being held around the UK, including 4 in Scotland.

1977 was another jubilee year, in this case it was the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, and many local celebrations were held. Uniform ties were regularly altered in style between 1963 and 1983, going from the folded tie first to a mini necker which passed through collar loops, then a mini necker with a woggle, to a stitched cross over style tie which was held in place by the Promise badge, to a conventional rolled necker worn with a woggle – meantime the shirt went from full length, to 3/4 sleeve, and back to full sleeve, from chest pockets to waist height pockets to no pockets but a ‘pouch’ to wear on the belt instead, and from tucked in to worn loose to tucked in again with or without the belt being visible – but throughout, it was a uniform shirt in headquarters blue with a tie in Company colour and a brown leather belt!

1983 saw the Queen’s Guide Award moved to Senior Section, and the Blue Trefoil replaced with a new award, the Baden-Powell Trefoil.

1985 was the next big celebration year, with Guiding celebrating it’s 75th anniversary. Among the events was a large rally at Crystal Palace in the spring, organised by London and South East England Guides. Unfortunately the weather was unseasonably cold for the time of year, and this was not helped by some Guiders insisting on their Guides parading without coats, in their thin cotton shirts, despite the fact there was a fair bit of standing around involved and a cold breeze blowing – as a result of which there were several quite severe hypothermia cases amongst the Guides, and a major inquiry was held.

It was clear that the existing uniform was no longer suitable for it’s purpose (as well as becoming increasingly unpopular with members), so Jeff Banks of TV ‘Clothes Show’ fame was brought in to design something new . . . hence the radical change from air-hostess hat, blouse and skirt with tights and shoes – to baseball cap, polo shirt, sweatshirt, joggers and trainers.

Soon programmes too were changing in the late 1990s, with Trefoils being replaced by ‘Challenge Badges’ and a greater emphasis on the Patrol working together as a group to choose and carry out activities by themselves as a small self-managed group or gang, rather than on whole-unit activities as had increasingly become custom in many units, led by the introduction of the themed challenges, ‘Go For Its’. Community Action also became a distinct and highlighted part of the core programme, as in many ways Guiding sought to go back to it’s roots . . .

The Guide uniform changed again, in 2000, to a mix and match range in shades of navy, offering sweatshirts, rugby shirts and t-shirts, and later a zip hoody, navy polo, striped polo and t-shirt, worn with the girl’s choice of skirt, shorts or trousers. Patrols worked on themed ‘Go For It’ packs each year, with the ultimate aim being the gaining of the Baden-Powell award, named after the founders of Guiding. New innovations such as the Big Gig (and Tartan Gig) closed-doors pop concerts saw a modernising of the Guide section’s programme and image, and Guiding’s Centenary in 2010 brought a wide range of ‘Guide Getaways’ ranging from unit holidays to national and international camps within the UK, and International visits too.

A new uniform was introduced in autumn 2014, featuring a mix-and-match range in mid-blue with red trim, featuring a long-sleeve top, polo shirt, zip hoody, skirt and dress, to be worn with the girl’s choice of skirt, short or trousers. The fabric was deliberately chosen to be comfortable in different temperatures, crumple-proof and quick-drying, to cope with the rigours Guide uniform has to stand. The badges were redesigned too, with the Go For It cards being replaced by oval badges, the interest badges also being changed to a uniform shape and style, and the Challenge Badge colours being changed, to be star-shaped.

In Autumn 2016 it was announced that a new programme review was being launched, 50 years on from the last major review in 1966-68. It launched in July 2018, with a year-long transition period. It was out with Go For Its, Challenge Badges and the existing interest badges. Instead, there was a programme running through from Rainbows to Rangers, with 6 Theme topics. Within those topics the girls could work on new Interest Badges, and also on Skills Builders and Unit Meeting Activities. There was a Theme Award for completing each Theme, and ‘higher awards’ – Guide Bronze Award, Silver Award, and for those who completed all 6 Themes, Guide Gold Award.

Despite all the modern opportunites for travel, and the activities which technology offers, the No1 favourite activitiy for Guides – is still greenfield camping, and ‘Patrol Camp Permits’ are as prized as ever they were!

2020 brought some unexpected change for Guides – due to the Covid-19 pandemic, in March 2020 the UK went into ‘lockdown’, meaning everyone had to stay at home other than a maximum of one outing a day, for food shopping or exercise. This meant that unit meetings had to stop immediately. Some units went into hibernation, others were able to offer ‘meetings’ by newsletter, social media posts, or videoconference. In August units were permitted to resume meetings outdoors, but this often involved everyone wearing fabric or surgical masks which covered the mouth and nose, and remaining two meters apart from each other.- and after a few months this stopped with a second lockdown, which lasted into 2021. Spring 2021 brought a slight easing of lockdown with outdoor meetings becoming possible where risk assessments allowed, and from August indoor meetings were permitted. But this required units to find premises willing to host them, and enough staff, and while some units could start that autumn, others had to wait until January or Easter 2022, and some did not re-open.

Because of the difficulties, the programme requirements were trimmed temporarily, to 4 out of 5 Skill Builder activities rather than all 5, and an hour fewer of Unit Meeting Activities for each theme. Although it was originally announced that the changes would be temporary until July 2022, it was announced in June 2022 that the changes would be made permanent.

A further change came in March 2023 with the introduction of new branding across Girlguiding UK. The first step was the introduction of new Promise Badges, featuring the new logo in section colours. We were also advised that uniform would be changing – but not for two years, and there would be a transition period at that time.