So Guiding started in 1910 – and within a year, the first unit catering specifically for disabled girls had already been opened at a residential hospital. In those days it was not uncommon for physically disabled children to be entirely confined to a hospital or institution, or to their house – and sometimes to a room or even to a bed within it, for years, if not for life.

There was no legal requirement for any formal education to be provided to disabled children, regardless of whether they were physically or mentally disabled, so most were not able to access any formal education unless their families were in a position to pay for a private tutor. Equally, most local authority schools weren’t accessible to anyone with any mobility problems, or any hearing or visual impairments. There was no funding to help families look after their disabled children, so where families were of limited means, looking after a disabled child who was likely to become a dependent adult could be especially difficult, or impossible. The luckier children with disabilities spent months or years in hospitals or institutions where there was specialist care for their physical or medical health needs – but even here, formal education was either limited or non-existent, and there was usually no attempt made to prepare the children for independent life beyond the institution, either in terms of academic education or in domestic skills, even in the case of long-stay patients.

There were some specialist boarding schools catering for either blind or deaf children, but the focus in them tended to be more on learning to cope with the disability once they left the school, and involved training in the limited range of careers which it was thought that they could excel in, rather than there being any particular focus on academic subjects, or any thought that going on to mainstream further education might be an option. Many schools for the deaf focussed entirely on teaching speech and lipreading, whilst actively discouraging, and in some case banning, sign language.

Thus for members with disabilities, Guiding could be even more of a lifeline than it was for those in ‘ordinary’ units, in that it offered a rare chance for disabled children to be the same as other children of the same age, with the opportunity to do the same activities as them, and pass the same tests as other girls their age did – being challenged to be as capable, or in the case of handicrafts, sometimes to be more capable than their peers. So many girls with disabilities were joining Guiding, that in 1921 a special section was set up within Guiding, which was called “Extension Guides” because it ‘extended’ Guiding into institutions and to individuals that mainstream units could not reach.

There were various forms of Extension unit. In hospitals dealing with physically disabled children, a special Guide Company, and in some cases also Brownie Pack, could be set up to cater for the patients, often with visiting Guiders who attended once a week, bringing something of the outside world with them. Activities from the handbooks were adapted just sufficiently to enable the girls to carry out as much of the regular programme as was possible – placing an asbestos sheet on the bedclothes would enable a bedbound Guide to lay and light a small fire, signaling buzzers could be used to send Morse messages from bed to bed, scrapbooks and nature samples such as pressed flowers or leaves donated by country units could be used to help girls (a number of whom had never seen any birds, animals or plants beyond any visible from their bedroom or ward window), to learn some nature lore – it was found that most of the Second and First Class challenges could be achieved with minimal adaptation, and several with no adaptation at all – and it’s important to recognise the value of that rare experience of sameness and equity.

There were also ‘special schools’ for girls with behavioural difficulties – so there was a particular type of Guiding, “Auxiliary Guiding” which could be set up, available as part of the programme of activities at the institution, and providing an optional scheme which offered privileges and attainments to the girls resident there.

And for those who were housebound, there were Post Guide and Ranger units – the Company meeting took the form of a scrapbook which was written by the Guider. The Patrol Leaders each received their copies from her and added in their pages of Patrol news and activities, then forwarded it on to their Seconds, and so it would pass in turn through all the Guides in each Patrol. It would contain activities for each Guide to tackle and enclose her results in the little envelope gummed to the back, there would be quizzes, puzzles and challenge work, adapted so it could be done despite the girl’s restrictions. When the last Guide had completed her activities, she sent the letter back to the Guider, who could track progress, and prepare the next letter for sending out. Where possible, local units were encouraged to ‘adopt’ any Post Guides living in their area and arrange to invite them along to visit occasional meetings, join in with outings etc. The big problem the Post Guide units faced – was in actually finding their potential members. After all, they were mainly dealing with girls who were housebound or even bedbound, and who weren’t registered with any local school, so Post units often relied on local Guides and Guiders passing on details of girls they knew living nearby who might be eligible to join.

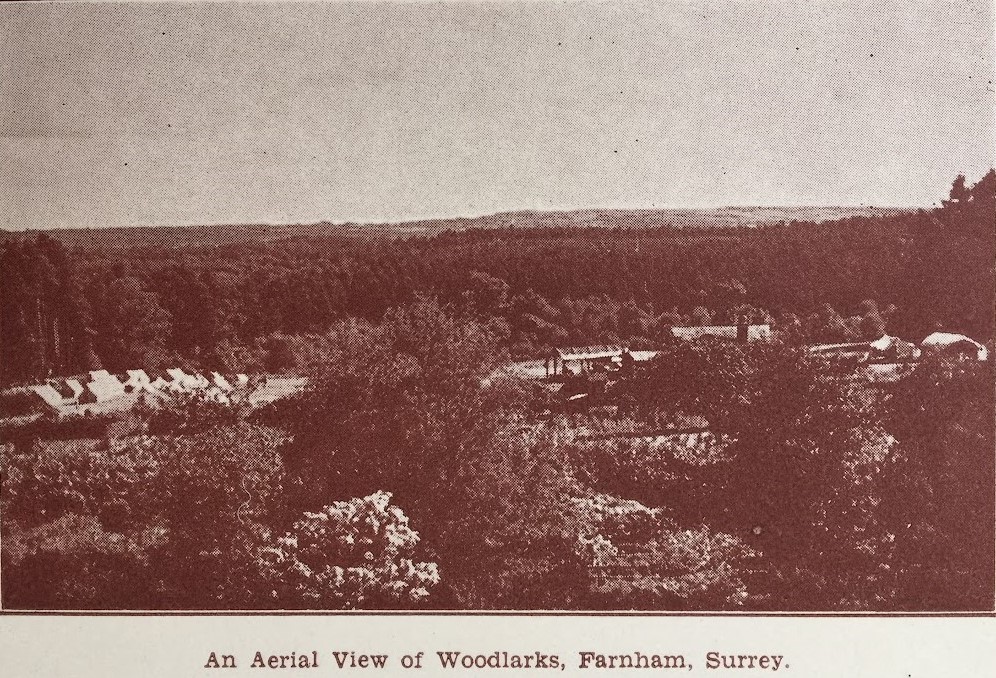

Soon, in spite of the difficulties, the reach of Extension Guiding had spread far – in 1931 there were 181 Guide Companies in the Extension Branch, and 41 Brownie Packs. Valuable work was also done by Dorothea Strover, who with her husband, set up the ‘Woodlarks’ camp, which offered the opportunity for Extension Guides to camp for a week or fortnight on a specially-built campsite. Camping at Woodlarks was run on the buddy system, with each Extension Guide being paired with a helper, who was encouraged to step back and let their partner do as much as possible, only helping where necessary. Many of the Extension section campers returned year after year, becoming camping experts, and many of the helpers, too, continued to serve for many years.

There were published resources for extension Guides and Guiders. The Extension Handbook gave suggestions on adapting the programme to enable girls with different disabilities to participate in it equally, and also gave details of the special Extension proficiency badge syllabuses, and adaptations. There were games books which gave suggestions of games which could be used by those who were bedbound, or blind, or deaf. And there were publications such as “The Venture”, a joint magazine for Scouts and Guides, which was printed in braille.

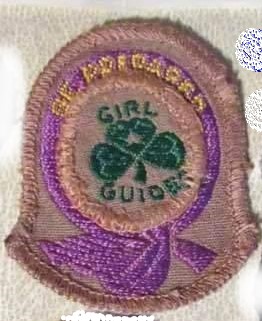

Prior to 1968, Extension Guides wore the special Promise badge shown on the right, which was similar to that for Air Rangers, but had lilac coloured enamel rather than the sky blue of the Air Ranger badge – they can be very similar and easily confused.

There was also a special First Class badge which Extension Guides could gain, shown on the left, and special All-Round Cords too – originally in mauve, later in blue.

Those who were able, were allowed to work for the green or red First Class badge instead if they wished. Those who did red First Class could be eligible for gaining Queen’s Guide – which mauve or blue cords did not allow.

A special range of interest badges was available for Extension Guides. In 1939 these badges were: Ambulance, Collector, Gardener, Handicraft, Hostess, Language (for the deaf), Observer, Sick Nurse, Sportswoman, and Thrift.

Over time more badges were added, and the list included Ambulance, Braille, Brushmaker, Camper, Collector, Gardener, Handicraft, Homemaker, Horsewoman, Hostess, Language (for the deaf), Netter, Observer, Potter, Sick Nurse, Sportswoman, Swimmer, Thrift and Weaver

The proficiency badges initially had mauve stitching, later blue, rather than the green of regular Guide badges. This did not preclude extension Guides from earning the mainstream badges too – yet for some badges (such as craft) testers were usually far stricter with the Extension Guides, because they had higher expectations of Extension Guides’ ability at handicraft than of those in ordinary units – expectations which were usually met, with pride!

Through the 1920s and 1930s, the tricky question of employment for many Extension Guides was a major issue, at a time when supported employment was rare, there were no benefits payments for disabled people, and the general unemployment rate in the UK was extremely high for everyone in society, disabled or not. In society at large, the disabled had long been viewed as a lifelong burden on their families, with the responsibility for their care and the expense of supporting them falling firstly on their parents, and then on their siblings, and eventually perhaps their siblings’ children. So Guiding set up a ‘handicrafts bureau’ – which provided training in practical crafting skills tailored to the individual, helped the Extension Guides to source craft materials, and then collected and sold the produce on their behalf through the bureau, enabling the Guides to earn some money for themselves, and contribute a share to their family’s household budget. Local Guiders were encouraged to visit the Extension Guides in order to teach them craft skills, deliver supplies, and collect finished goods to send to the bureau, and local Guide Companies were encouraged to ‘adopt’ and befriend the Extension Guides, and perhaps invite them along to occasional meetings, or to camp if possible. Because many of these Extension Guides had long hours of time available with nothing else to occupy them but practicing and developing their craft skills, they were able to produce work to a very high standard, in spite of physical difficulties; in many cases whilst battling discomfort or physical pain. The bureau continued to operate for many decades until mainstream employment provision meant the numbers participating eventually dwindled to single figures, and it finally closed.

As well as doing regular unit activities, Extension Brownies and Guides were often able to go to special Brownie Holidays or Guide Camps, with adaptations kept to the minimum necessary. Altar fireplaces naturally lifted the fire up to a suitable height for someone in a chair or wheelchair to tend it, frame tents could be useful in making enough space and height for physically disabled girls to move around within the tent and sleep up on a camp bed rather than at ground level – and the experience was especially valuable for girls who rarely got to leave home at any time. Many blind Guides were expert campers through having to become familiar with every aspect of tent pitching and tent care by touch.

Over the years, echoing progress in society, disabled members within Guiding have been integrated into mainstream local units, but a small number of specialist units remain, often linked to hospitals and residential schools for the disabled, such as with the Guide unit linked to the Royal Blind School in Edinburgh, and the units at hospitals such as Great Ormond Street in London, which cater both for long-term in-patients and those Guiding (or Scouting) members who are in the hospital for only a few days or weeks. These units aim to offer as wide a range of activities as would be found in any other unit, with members tackling the same challenges and awards, and having the same opportunities.

Increasing numbers of Leaders who happen to have disabilities are involved in Guiding too, in mainstream units particularly, and much work on inclusion and providing opportunities has been done. Each Guiding County should have an Adviser for Members with Disabilities, to offer help and support to unit Leaders on how to support the disabled members within their units, in order to make the local units as inclusive as possible. Leaders with disabilities have gone on to be Leaders, Commissioners and Advisers . . .